Some people wake up every morning just to be meticulously unhappy. I say ‘meticulously’ because you can see the satisfaction they get from it, how deliberately they seem to prepare themselves for their gloom.

These are the kind of people who, fueled by the negative feelings they harbor toward life, have no hesitation in pulling both themselves and everyone around them into that same downward spiral. They complain about everything, and when any chance at happiness comes their way, they turn it down without a second thought.

They may be sixty years old, yet they’re still fixated on how their mom or dad ignored them at ten, endlessly crying ‘my trauma this, my trauma that’ for the whole world to hear. I used to try to help people like this, but eventually I realized it was a pointless effort. Their parents might have been gone for forty years, and they’re still fighting them in their head! At some point, you can’t help but think, ‘Let them deal with it themselves’

According to psychiatrist Alfred Adler, the founder of the school of Individual Psychology, ‘A person is not a product of the past, but of the choices they make about that past.’ In other words, pain, loss, and abuse from the past are, of course, impactful, but they do not determine our fate. What truly matters is how an individual interprets those experiences. People can use their traumas as excuses to avoid taking responsibility, and they certainly do!

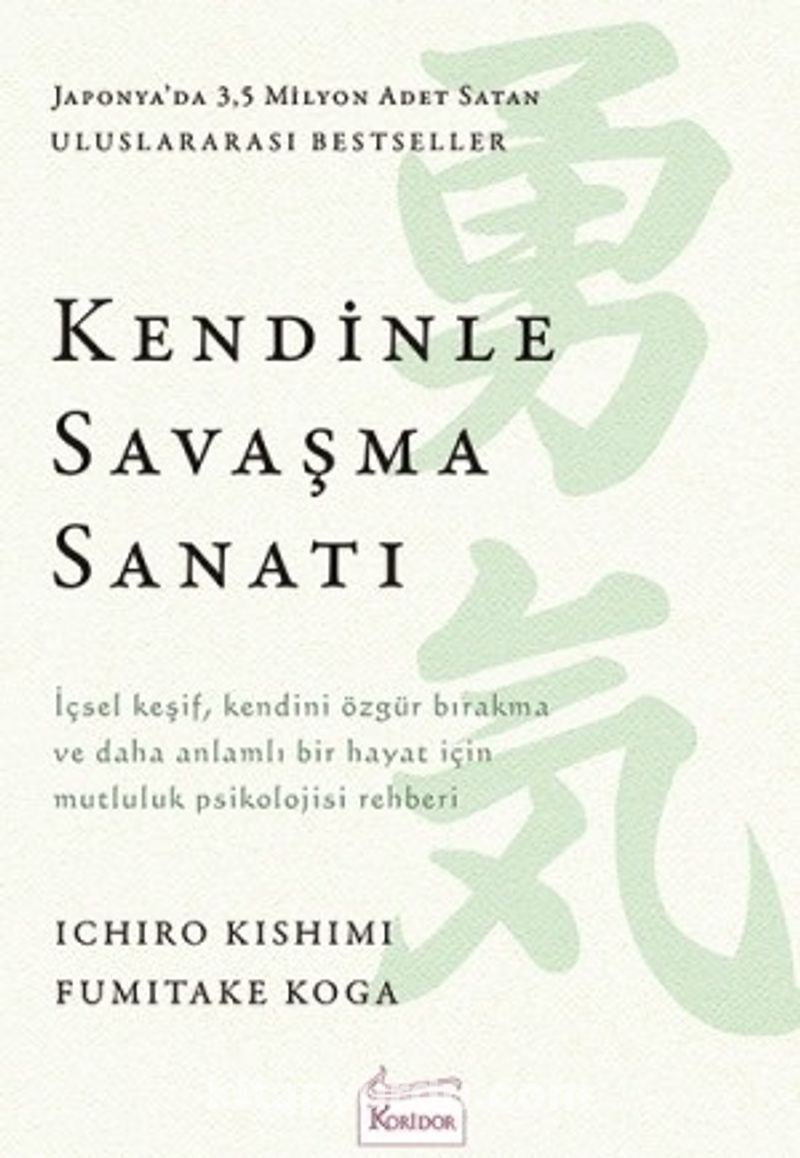

Japanese philosopher and Adlerian psychologist Ichiro Kishimi and author Fumitake Koga’s book ‘The Courage to Be Disliked’ (Kirawereru Yūki) unfolds as a dialogue between a wise philosopher and a young man, set within the framework of Adlerian psychology. The book is written in a clear, easy-to-grasp style. You can think of it as a guide, profound yet simple. As the young man and the wise philosopher discuss topics such as how past traumas do not define you, the freedom found in not seeking others’ approval, the psychological meaning of responsibility and freedom, the courage to accept yourself and not control others, and the two very different concepts of feelings of inferiority and the inferiority complex (as well as feelings of superiority and the superiority complex), the reader feels like a third person sitting alongside them, listening in.

This book, where Adlerian psychology with its solution-focused, optimistic, and goal-oriented perspective that sees people as agents rather than victims comes together with philosophy, has a sequel titled ‘The Courage to Be Happy’. I will write about that one once I read it.

Since We’re in a Black Hole, Then Welcome It Is

“Because of the ‘chronic dissatisfaction’ they’ve planted at the center of our lives, we’re forced to keep running. They’ve trained us so well that the goal is no longer to arrive anywhere but simply to keep running. That’s why we’re so exhausted, because no matter how much we run, we never seem to reach a destination. If you also feel like there’s a black hole inside your head, swallowing everything from time to time, welcome to the club.”

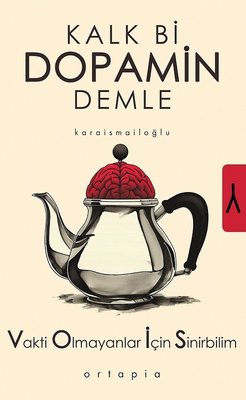

I read this line on the back cover of Kalk Bir Dopamin Demle (literally ‘Brew Yourself a Dose of Dopamine’) by Dr. Serkan Karaismailoglu and Dr. Ali Ismailoglu, immediately thought, ‘Yes. I absolutely feel welcomed,’ and bought the book.

I don’t know how it happened, but time feels like it’s racing past at ten times the speed for me. I’m forever dashing to the next thing, and before the first sprint is over, the second one begins, then the third, fourth, fifth…

In Kalk Bir Dopamin Demle, the Karaismailoglu brothers first lay out what dopamine actually is, and then show how we get caught in the dopamine trap. In other words, it explains why we keep running yet never seem to arrive anywhere!

In this book, which lays out modern-day struggles like stress, addiction, and attention deficit, offering solutions by illustrating how the brain works, questions such as why we procrastinate, why we’re unhappy, and how dopamine, serotonin, and oxytocin influence our moods and decisions are explored not with dense academic jargon, but through relatable, everyday examples. For those interested in neuroscience, it is both humorous and informative.