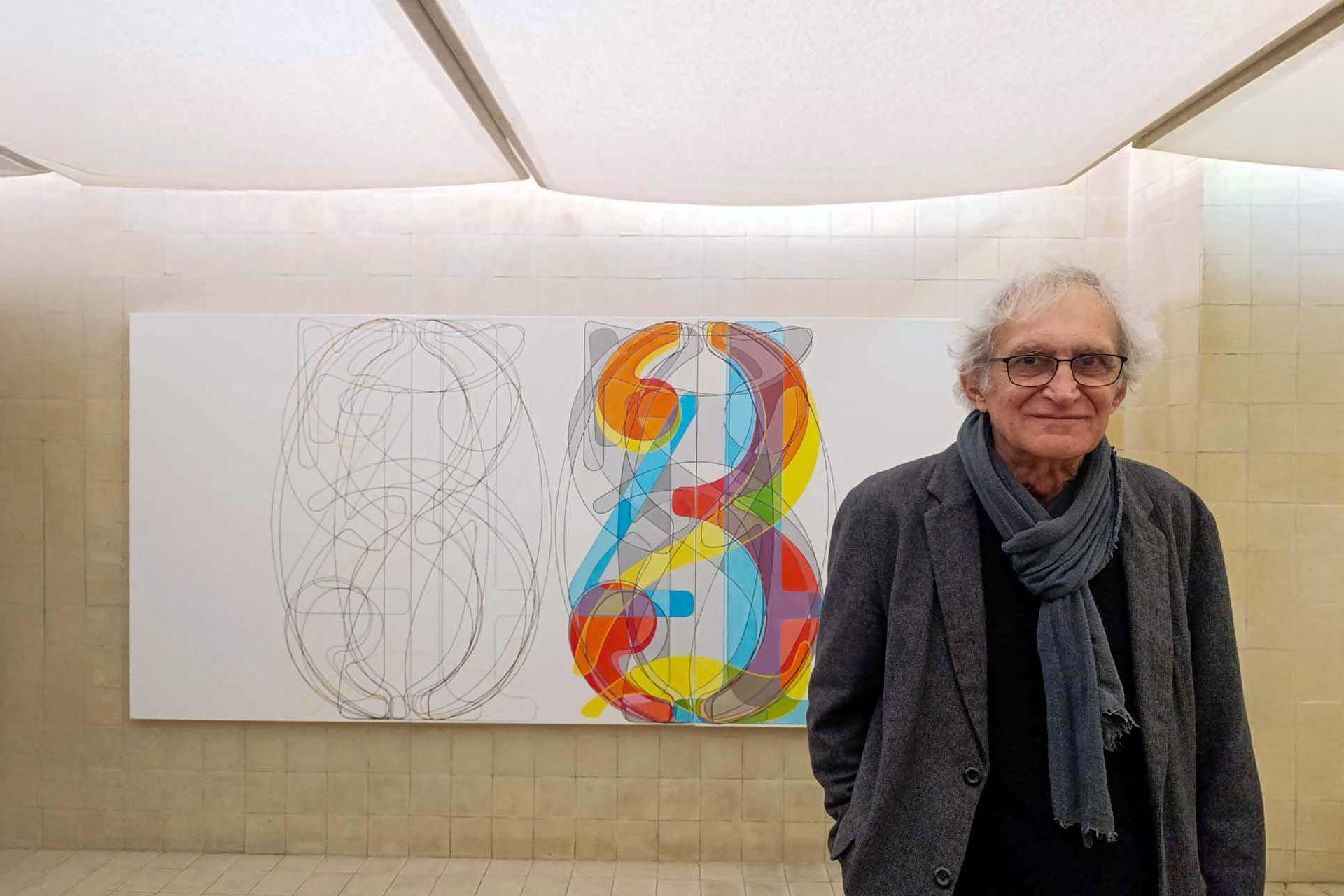

One of the distinctive names in contemporary Turkish art, Serhat Kiraz, confronts the audience with the transformation of form and content through his exhibition “Transform” at Macka Art Gallery. Having held his first exhibition at the gallery in 1984, Kiraz—who has become part of art history with the Art Definition Group, of which he is a founding member—speaks about his variable, concept-heavy exhibition, woven with numbers, forms, and colors and rich in footnotes: “I made this exhibition so that everyone can see it in succession. What multiplies, and how? What should not be multiplied? These are decisions that need to be made. How will you distinguish between the ‘same’ things that are shown to us in different ways? In the end, nothing really changes in the intellectual structure,” he shares.

In contemporary Turkish art, artist Serhat Kiraz, who—alongside Sukru Aysan, Ahmet Oktem, and Avni Yamaner (listed alphabetically by surname)—was part of the Art Definition Group (S.T.T.) (1), a collective that marked a defining historical juncture, has opened a new solo exhibition titled “Transform” (Variable Form) at Macka Art Gallery (MSG) (2).

The exhibition, hosted at MSG—whose logo bears the signature of the late master graphic designer Mengu Ertel and which was taken over by Didem Capa from Rabia Hanım in 2021—was attended by many of Kiraz’s students and close acquaintances, including Rabia Capa and the gallery’s architect Mehmet Konuralp, as well as S.T.T. member and artist Ahmet Oktem, art historian Ebru Nalan Sulun, Mine Art Gallery founder Mine Gulener, and other creative companions and friends such as Tayfun Incedayı, Hakan Demirel, Ani Celik Arevyan, Fatih Kizilcan, Esra Carus, Rabia Seyhan, Tunç Ali Cam, Banu Çarmikli, Cem Odman, and artist Halil Altindere (and his family).

In this “living monument to art”—realized in 1976 in Macka, Istanbul by Varlik (Sadikoglu) and Rabia Capa, and designed by Senior Architect Mr. Mehmet Konuralp—it was announced that Kiraz’s new exhibition, woven together through drawings, installations, and acrylic series, would remain on view until June 7, 2025.

Kiraz had also presented his very first solo show at MSG, titled “Dosem,” back in February and March of 1984 (3). In that exhibition, he used contact prints in a site-specific installation format. Now, with his 2025 exhibition “Transform,” the doors of the gallery open once again—in the season of cherries—for visitors. The event once more fostered an atmosphere in the gallery akin to a visual, conceptual, and plastic research laboratory.

As is well known, conceptual art (4) began to be used in the 1960s to describe artworks that no longer presented themselves in traditional artistic forms. Also referred to as “idea art,” this movement’s artists do not set out to create a painting or sculpture and then generate ideas toward that end. Instead, they aim to express their ideas using materials that go beyond conventional tools and forms. In short, thinking about art becomes indistinguishable from making art itself—and becomes the invisible social and cultural glue that binds one to it.

Serhat Kiraz, who remains loyal to this form of art known for its ability to manifest itself in any medium or material, continues a tendency that reaches back to the group exhibition “On Image and Reality,” (5) which he held with S.T.T. in 1978 at the Istanbul State Fine Arts Gallery. In doing so, he persistently and coherently instrumentalizes elements such as original vs. copy, illusion vs. reality, fact vs. truth, or representation vs. correctness in his artistic practice.

In his new exhibition spanning April, May, and June 2025, the artist—born in 1954—continues to bring together numbers and colors on paper and canvas, exploring the traces of numbers and the coded meanings of colors within the history of civilization and graphic art memory, all with an analytical and ironic approach.

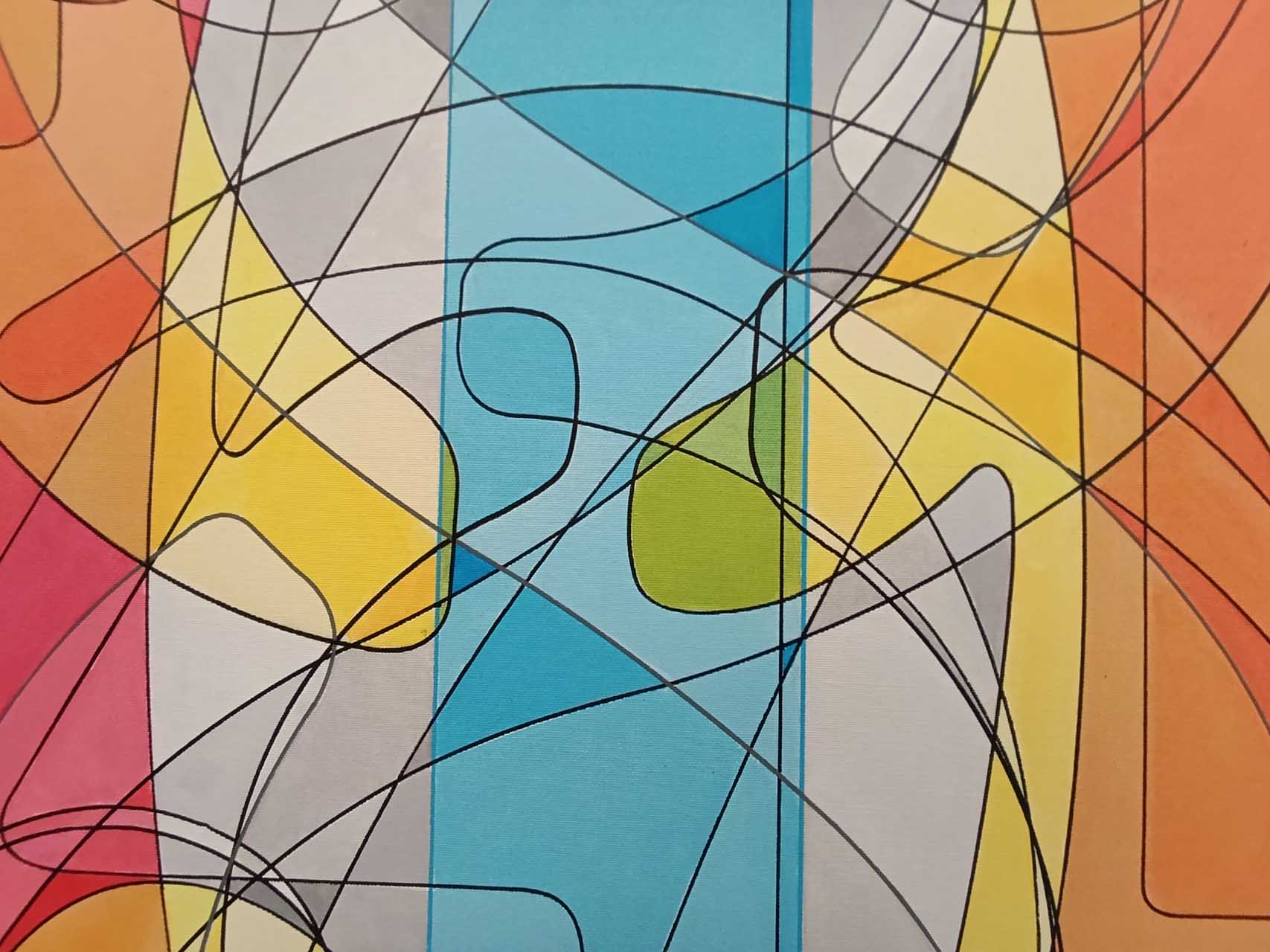

The exhibition foregrounds Kiraz’s horizontal and minimalist abstractions—both singular and plural, colorist and graphically dense—derived from massive number “skeletons” that he has superimposed repeatedly. In this new show, which demands time, curiosity, and patience from the viewer, the artist merges with the observer in what could be seen as a perpetual compulsion of existence.

Kiraz especially examines—and in a sense, generates—the boundaries of visual expression and representation through his “color pairings,” remaining faithful to the primary colors foundational to graphic art. These pairings, which facilitate our perception of nature, probe the organic states and expressions of transformation in combinations like green and red, blue and white, yellow or green and gray.

According to information provided by MSG, in this exhibition Serhat Kiraz brings together the ten basic digits, from 0 to 9, which form the foundation of the decimal system, with the three primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) in an algorithmic structure. “…In the light of visual analysis, coding theory, and semiotics,” Kiraz “overlaps digits with the three primary colors to create layered and semi-transparent effects. In a triplet coding system where each digit operates within a three-valued logic, specific digit combinations produce secondary or tertiary colors, while intersecting regions where digits meet without full overlap generate new colors. Gray areas and the different tones he uses for colors represent zones where the artist steps outside the algorithm, pushing the boundaries of uniqueness.”

Also according to MSG, “…the visual algebra and color mathematics embedded in Serhat Kiraz’s works evolve into a visual symphony, resonating with the harmonic tones of musical triads. Within a structured algorithm, the artist reimagines mathematics, color theory, and aesthetics as a fully sensory and immersive experience, offering new perspectives on what we think of as ‘standard numbers.’”

In addition to this institutional description, Kiraz is known for a style that—in effect—portrays the subjective states arising from the slippery terrain between truth (the objective) and the state of being real (reality) in his art. With a style that is minimal, resonant, and structural, where the two semiotic cats known as ‘concept’ and ‘form’ are forever chasing each other’s tails, Serhat Kiraz’s works invite viewers to explore and interpret concepts such as logic, reasoning, archiving, memory, derivatives, and roots—bringing these abstract elements into open dialogue.

Indeed, when we look at Kiraz’s generation, one is reminded of artists like Joseph Kosuth, an American artist of comparable age, whose works similarly experience art not as an emotional expression but as a source of knowledge and interpretation, merging image and information. Kosuth—whose works have also been exhibited in Türkiye at Borusan Art Gallery and Kuad Art Gallery under the curatorship of Beral Madra—comes to mind naturally in this context.

Likewise, the 1980 exhibition and documentation titled “Text as Art,” presented by S.T.T. with guest artists Alparslan Baloglu and Ismail Saray, explicitly included Kosuth as well as figures like Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, and Robert Morris among its references (6).

Yet with his distinctive plastic language, Kiraz exhibits a “resonant” attitude—one that not only aligns with contemporary music (such as John Cage) and jazz (like Miles Davis), but also, through the transcendental derivative potential his works evoke, gestures toward figures in classical music history like W.A. Mozart or Johann Sebastian Bach.

When we turn to a particularly insightful interview Kiraz gave 13 years ago to Ata Gur (7), we find one of the clearest articulations of what conceptual art is—and how Kiraz defines the relationship between his art and the truth it engages with:

“When they talk about conceptual art, this also comes up: you sit down and either make a sculpture or a painting, but if you want to say something, the message becomes: ‘What expresses it in the clearest, shortest way?’ If a sheet of file paper does that, then why go and turn it into something else? So, to what extent is the transformation of things really necessary? If something can already stand on its own… Then perhaps the whole idea of production needs to be reshaped as well.”

An object is learned through itself. I asked a question about how accurate it is to learn from the discourses on the object. So, what emerges is the idea that the truth is the truth itself. When you try to explain the truth itself, then you are operating in the realm of reality.

That’s why I made Visual “Illusions, Perception, and Reality”. I created very realistic paintings, with very realistic images, using many different media, in 1979. I placed numbers inside boxes. I said, “Let it be presented in different forms, the same image.” I painted it, showed it as a photograph, displayed it as a slide, and hung it on the wall.

When you place a photograph on top of the truth, you can solve the reality plane between the truth and the photograph. However, when you remove it, it appears realistic to you. In other words, no matter how realistic the image looks, if it is disconnected from the other, it appears as truth. In this way, when you assess something, you’re evaluating it based on other people’s value judgments.

However, when you are able to reach it yourself and observe it yourself, you can come to different conclusions. This structure exists within art. At the time, realistic art was common. When you look from the outside, what I did appears realistic; there are very realistic paintings in it. But to what extent does it reflect that truth? That’s the suggestion in the second phase, when it is confronted with the truth. Therefore, you start applying that strategy, to bring it face to face with reality.

At the opening of the “Transform” exhibition at Macka Art Gallery (MSG), Serhat Kiraz, whom we had the chance to meet, shared the following insights with us about the magnetic persistence in his work and the search within that persistence, spanning both his first and most recent pieces:

“Here, what we see is change, the change of form: Transform. We can say that the exhibition is based on the transformation of form. Additionally, the compatibility of that form with space is also addressed. When you look at the exhibition, you can see that I have created the number 10 using sequential numbers and the three primary colors—yellow, red, and blue.

For example, it starts with 1, 2, 3, and I have ‘coded’ it. I wanted the expansion in the coding system created on the computer to also be able to be expressed in this space. While the paintings initially appear to be the same at first glance, they start to change by repeating within each other. When the structures are stacked on top of one another, they create their own colors. There are 10 individual acrylic paintings on canvas, each 70 x 100 cm. In the last one, after the color changes following 0, 1, and 2, it transitions to another system. Therefore, we are presented with six patterns, which, in terms of their ‘ability to be instantly replicated,’ can actually become 60 pieces. But with mixed numbers, they can potentially reach infinity.”

As I observe the series (but unique) works of Serhat Kiraz in the MSG exhibition, a question comes to my mind:

“Is Serhat Kiraz at peace with the rational? Or does he perhaps live with a lifelong crisis and doubt about the rational?”

With his usual straightforwardness and generosity, Professor Kiraz responds:

“It’s possible. For example, in a past exhibition I held in Germany, I had built a large ‘structure’; this structure was a study on the existing layers and structures of the universe to understand it. This was based on an old Platonic thought system.

But what you’re referring to in this question, isn’t it ‘outside of everything’?

I mean, we are between these two positions now, and we still can’t decide which one is correct. Scientifically, we can’t decide if we truly have all the knowledge or not!

What you’re talking about also takes place within this search; I, too, am trying to explore these systems. This same shifting condition also appears in linguistics. According to linguists, if you think about the forms of stories produced according to their localities, times, regions, and even religious origins, I also thought about how I could fit this into this space, and with this exhibition, I developed such a thought.

Let’s look at the past in art: Let’s ‘revisit’ that text: What does Walter Benjamin say in 1935? “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (8). I, too, made this exhibition so that everyone could see it, so that it could be experienced by everyone sequentially. How does it multiply? What should not be multiplied? These are decisions that need to be made. How can you distinguish the ‘same’ things that are shown to us in different ways? In the end, nothing changes in the conceptual structure. If there is change, it occurs technically.”

References and Footnotes:

- https://www.sanattanimitoplulugu.org/STT’nin%20Tarihi.htm

- https://www.mackasanatgalerisi.com/

- https://www.mackasanatgalerisi.com/2021oncesiturkce/Exhibitions/Serhat-Kiraz-1983–1984-0

- https://tr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kavramsal_sanat

- https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/207542

- http://kutuphane.arter.org.tr/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=12967&shelfbrowse_itemnumber=12896

- https://istanbulmuseum.org/artists/serhat%20kiraz.html

- https://acikders.ankara.edu.tr/pluginfile.php/96489/mod_resource/content/0/Estetik.%208.%20Hafta.%20Benjamin.Tekni%C4%9Fin%20Olanaklar%C4%B1yla%20Yeniden%20%C3%9Cretilebildi%C4%9Fi%20%C3%87a%C4%9Fda%20Sanat%20Yap%C4%B1t%C4%B1.pdf