“I think of my dream as 50% human, 50% machine.”

Multifaceted digital media artist Refik Anadol has a packed schedule. Most recently, with the support of Türkiye’s Is Bankası, Anadol created a living encyclopedia by transferring Türkiye’s flora and fauna into the digital realm. In the near future, he will showcase many projects at events like the Davos Economic Summit, the UN, and at MoMA (Sphere) in Barcelona and Shanghai. He also caught the attention of viewers in the skies with his project Inner Portraits, supported by Turkish Airlines, and left a permanent work at the Akbank General Headquarters. Recently, we had yet another extensive interview with Anadol, focusing on his agenda for yesterday, today, and tomorrow, as well as the latest global developments.

Anadol, who will be officially invited for the second time to the 19th International Architecture Biennale in Venice this May—an event organized by Italian engineer and architect Carlo Ratti—has already made history as the first Turkish artist to open a solo exhibition at Bilboa. As is known, Anadol is represented in Türkiye by Pilevneli Project, founded by Murat Pilevneli.

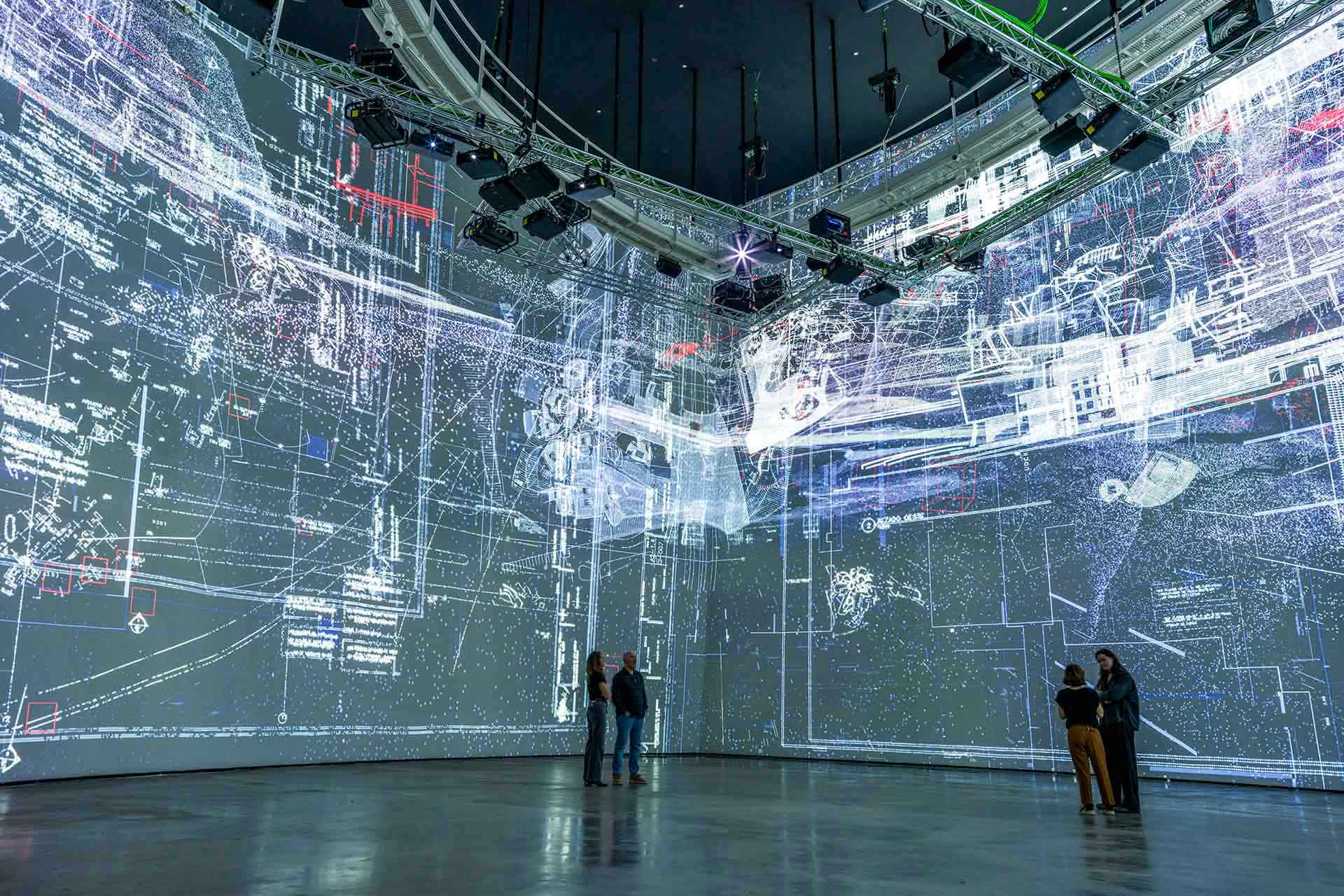

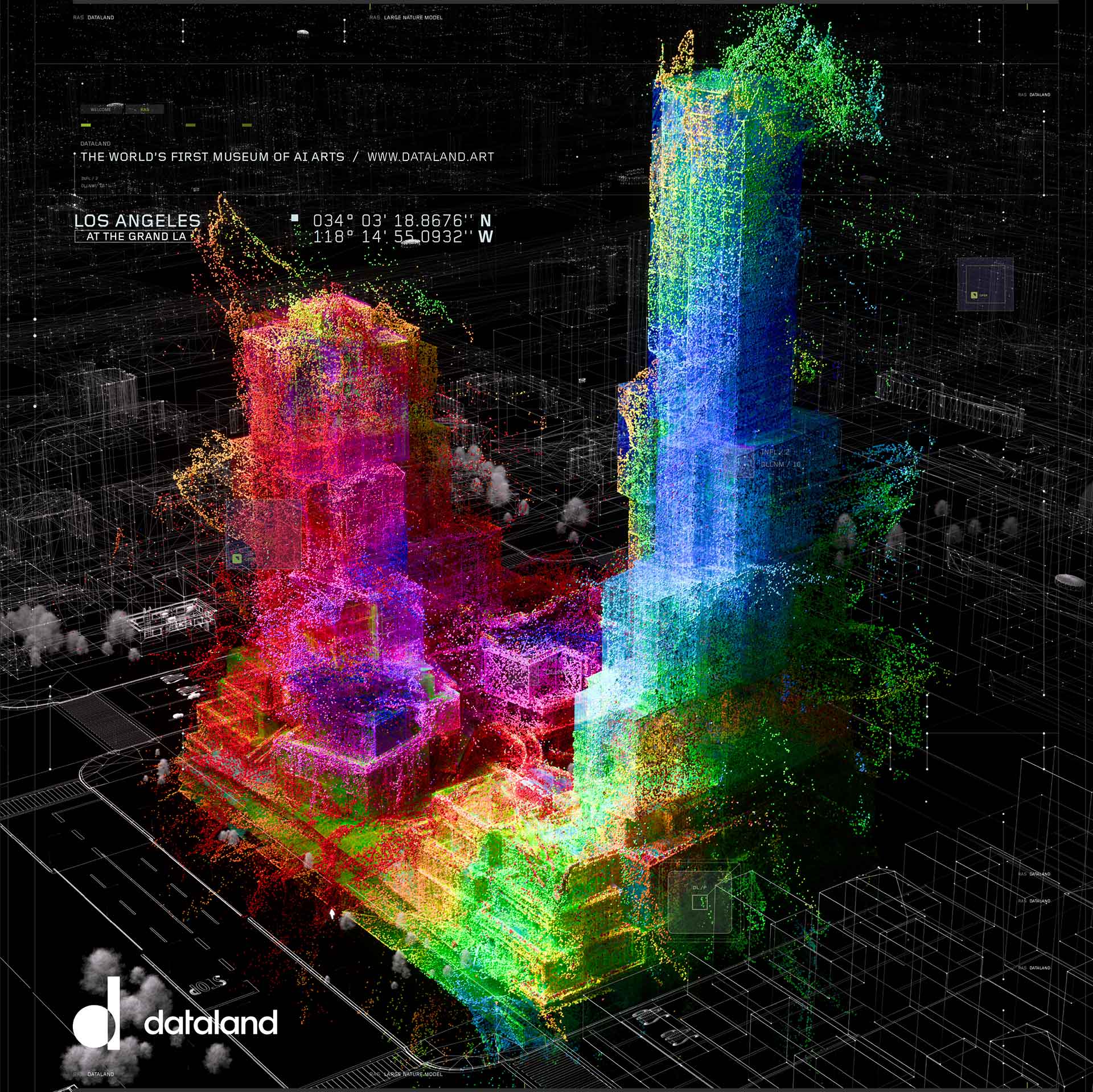

Anadol is also excited about the opening of Dataland—the world’s first AI/Machine Learning Museum, which will take place in Los Angeles this June. He shares this excitement with his life and professional partner, his wife Efsun. Working in an international workshop composed of a multicultural team at his LA studio, Anadol reflects on the critical feedback and thought-provoking questions raised by his global projects, including the Wide Nature Model at NVIDIA 2024 and Sphere in Las Vegas. He shares his insights with us as follows:

After the opening of your installation project In Situ (1) at the Guggenheim Bilbao, which will be on display until October 19, 2025, you returned to the US with your work partner and life partner, your wife Efsun. Thank you for taking the time to speak with us again. Let’s get straight to the point: What’s the agenda in Spain? Is Europe being discussed there as well?

Very interesting! This time when I went, the first question I got was, of course, about (Donald J.) Trump. They asked, “What do you think?” Many journalists came to Bilbao from Germany as well. Most of them had already experienced a lot of tension due to the elections there, and to be honest, I couldn’t follow much of it. While working on my Guggenheim project, I couldn’t spend a single minute on the internet!

However, this time when I came to Spain, they were asking questions like, “What do you think about where the US is heading? What about the future of Artificial Intelligence, and the leadership role the US has in this?” I particularly noticed this during the Action Summit that Macron invited me to. The US has a significant advantage in Artificial Intelligence. Even though China is trying something with Deep Seek (2), they are seriously behind. I think all of Europe is caught up in too many rules and bureaucracy. Of course, I’m not saying what they’re doing is bad, but somehow this series of rules has turned into a situation where they can’t take any steps forward. For instance, there have been many issues with data collection; AI networks aren’t being used. I didn’t know these things, but I realized them when I was there. Many people are seriously far behind on current models, not by days or weeks, but by months. So, it was really interesting. I understood how different it was this winter.

We, as humans, are right to both fear and not fear Artificial Intelligence today. Isn’t that so?

Absolutely. Very well said. From the very beginning, I’ve thought of my dream as 50% human, 50% machine. In my opinion, the future ahead of us marks the beginning of an era where machines can provide us with everything, at any time. A very, very small part of the world is aware of this. Therefore, this is a long journey, but the only reason the future can be logical, optimistic, ethical, and equal is understanding this. I don’t see any other option. The fears that arise when we set out without understanding Artificial Intelligence only grow bigger. Those who understand it have a greater potential. The faster someone can use AI networks, the faster they can learn experiences, techniques, science, and coding that they couldn’t before. Truly, the Internet today is full of people who can produce incredible software in 30 minutes. Every moment, every day, it’s like this. Humanity is experiencing such an incredible intellectual explosion right now. All of these things are happening simultaneously.

Fears are also emerging at the same time. So are illusions. Therefore, I believe, whether it’s good or bad, we’re in an extraordinary period. Because we are right in the middle of change. We are also in one of the most important times for art to share the “moment.” If art can understand this and convey to humanity the potentials, problems, interests, mistakes, and everything of this change and transformation, I believe art can reach a very meaningful place. I say this to support humanity. It’s not just a mental, intellectual activity; it has the potential to serve a function.

Your In Situ installation at the Guggenheim Bilbao, enriched with Kerim Karaoğlu’s sound extension, is being received with great acclaim. How did this project come to life? What is happening now? Also, you seem to work almost like a ‘Network’ source. Is there a clear set of criteria or priorities by which your projects are served to the world, the spaces, and visitors in your agenda? We see you serving your projects to the world like a conductor or composer. How do you design this ‘living organism,’ this composition over composition?

Such a great question. But some of these, in fact, are just parts of my dreams. While this is the case, some of them, like the MoMA NY project, can come to life through the combination of dreams. For instance, in the MoMA project, our curators Paola Antonelli, Michelle Kuo, and Stuart Comer, very specifically, during the pandemic when the museum was closed, their dream was clearly to create new work. And that was something wonderful. It was the result of the combination of their strengths.

The Guggenheim Bilbao piece, In Situ, is very similar: The museum’s esteemed director Juan Ignacio, after 30 years of helping establish and open the institution, decided with his team to support the creation of a work that could truly envision the future—something that had never been part of their collection before—during his final month at the museum, as a kind of tribute. Our curator was already someone highly aware and up-to-date on the subject. However, previously, no one had stepped into the digital field, except for Jerry Holzer. Moreover, I’m talking about works that are more related to light and spatial environments. The institution (Guggenheim Bilbao) had never engaged with a true digital artwork. They had never had that real experience.

And I think, actually, this began with the director’s very clear vision about a year and a half ago—“A new era is coming, a new period is starting; I’m passing the flag, and as I leave, we need to dream a new dream.” That itself was already an enormous space, because I even met with the curator in person about a year and a half ago. They showed me a gallery like no other! 16 meters high. With Gehry’s mathematical curves, called the compound, it’s almost like experiencing a kind of mental orgasm. Aesthetically, it was amazing. The acoustics, everything, was perfect.

You’re referring to architect Frank O. Gehry’s “architectural magnetism,” right?

An amazing gallery! I mean, I don’t know of any other gallery or museum in the world that is as pure and clear as this one. I’m not talking about a spiritual or mystical space designed 30 years ago. I can’t recall a recent architectural design, created within the concept of a ‘museum,’ that is anything like this. And it was incredibly impressive. They asked me, “What would you like to do in this gallery? What kind of sculpture should we place? What kind of screen should we put?” I told them, “If I, as a hero of Frank O. Gehry—especially after 2018—have the chance to reference him once again, I wouldn’t use that opportunity on a screen. I would want to make the space itself feel like the ‘canvas’ for this idea.”

When they asked, “What do you mean by that?” I said, “I want to turn the walls of the entire space, from floor to ceiling, 360 degrees, into the canvas where you could hang the paintings you’ve been able to display for the past 30 years in this space.” Of course, they were surprised at first. The space is so large. It’s an impossible scale. It takes four days to paint! They asked, “How can we do this?”

This journey began like this… Thanks to them, I immediately said, “I want to reference Frank O. Gehry because at the core of this work, like the ‘Bilbao Effect’ this space created, I want to be part of an idea that revitalizes the city and sends a message to the world.” They immediately emailed Gehry’s office, and the response was very positive. In their reply, it said, “Of course, we know Refik, he can use the data, he can do whatever he wants.” From that moment, the idea immediately took shape. We worked with 50 projectors. I can say that this is the highest resolution we’ve ever worked with, the largest channel size, and the most comprehensive piece we’ve made to date. It’s the largest work where light is used as material. In my opinion, it’s a pioneering work in the art world, especially in the museum world.

Lastly, thanks to the Google team… Yes, I know the critiques of working with Google. But I want to be very clear: we only received support from Google, which works entirely with renewable energy and doesn’t harm nature. Before and throughout the exhibition, we also use a ‘Data Cloud’—a cloud computing network in the Netherlands that runs solely on wind energy. If we multiply the energy consumption of an iPhone for a year by four, that’s the amount of energy this exhibition will use, and it will continue to “dream” for a year. It will not repeat itself; it will dream with a living architecture.

Also, together with Kerim Karaoglu, who I’ve been working with for 14 years, we didn’t hesitate to gather the data on the materials, interiors, and acoustics of Gehry’s buildings. We recorded sounds of titanium, sounds from the wooden structures and timbers used, and how the building’s relationship with nature—the wind, the rain, and different times—creates certain sounds. We also had the chance to capture frequencies we can’t normally hear. This led to a very unique and fascinating sound design that I had never heard before. We were able to bring everything together.

Sound, image, smell… These are dominant senses, and indeed, even hearing and touch have reached a level where they are now considered limbs of culture and art. In this context, we are familiar with art’s collaboration with Google Arts and Culture, which works with all museums and institutions. So, what are your observations and criticisms regarding Google’s globally debated “algorithm,” that is, the data sorting “fault”? The claim is that information and data, which could ideally be improvised, independent, or even critically approached, are being owned by Google in such a universal, “authoritative” way. Doesn’t this concern Refik Anadol at all?

Of course, Google Arts and Culture is a free and open archive for everyone. And of course, any large entity that possesses big data concerns me. It’s not just Google; this includes Microsoft, other search engines, and even many companies from Türkiye. Anywhere data is used to produce products and services, this issue exists. Google is one of the best and most pioneering in this. However, what excites me is this: What do these institutions give back? Can they provide open-source code? Can they provide free computing power or information stacks that are inaccessible to us? Are they just in a model that doesn’t give, or are they actually open-handed in a different way? Do they support a domain? Do they provide free applications for education or other fields? This is how I try to understand them. And the closer I look at these institutions, the more I can see what these open-source, multi-billion-dollar institutions are not doing that they could. None of this is secret or closed.

I have also seen that these institutions have dreams that are not solely focused on money. On one hand, yes, the products and services they offer to humanity, as intelligent institutions that can understand the materialization of data, are always open to scrutiny. Ultimately, all of these services are systems that make us question both their privacy and our free will. As a result, this could be a food service, a transportation service, a research service, or a communication service. It could even be a social media service. At their core, since they are all based on ‘data,’ we need to place them all on the same level. So, when using these tools and services, if we, as users, can understand the intention of the producer of the tools and services, and if we are conscious users, then there is no problem. However, if we are unconscious users, of course, there is a problem. What I mean is, if we can imagine two types of users—conscious and unconscious—then we know that a conscious user can always use these systems well in their own domain.

The real question here is how we can be more conscious of these products and services, and whether art can make us more conscious in this domain. I am always asking what the questions and artworks are that would allow art to do this. If an AI can learn, can it dream? Because the way AI is used mimics reality. But what excites me as an artist is not that. On the contrary, what exists beyond reality? Therefore, it never satisfies my mind. We need to transform it and see it again, apply it. In a way, it’s a form of activism, but not in the way we know it. The first form of activism we think of is no longer the same. And it doesn’t need to be because we’ve seen, as much as we’ve researched, that the things that have existed have not created any change. So, in a new world, the way we question institutions and organizations under a new heading could, and should, change.

For example, I’m sure the six major institutions I work with are currently questioning both their data and ethical decisions. They are questioning how to do computing without harming nature. I’ve been able to measure that I have succeeded in this, and until today, I haven’t been able to measure that any activism has been able to achieve this. That is, I haven’t seen a work of art activate such a movement in the field of computing that respects data, privacy, and nature. At least not in the event invited by Macron, or at the UN. I didn’t see it in Davos either. The good news, at least, is that I can say this approach of mine ‘works.’ I can say it has an impact. Criticizing what happens to data, etc., of course, is a method. But being able to discuss the labor and its surrounding aspects is also important.

Does Refik Anadol act like a sort of ‘Trojan Horse’?

But art, it always behaves like this. Artists have always been the ‘alarm mechanisms’ of humanity. This is not something that changes. For an artist to be an artist, they must be the ‘alarm mechanism of humanity.’ They must be the compass for people. I don’t know if this is a necessity, but the feeling that comes from my heart, from within me, is that it’s important not to keep the work I do, the tools I use, the technique, the method, egocentrically to myself, but to share it. Of course, this also comes from my role as a teacher. As you know, I am also a teacher. I’m not just an artist, and my intention is not to keep my technique and my intent to myself. On the contrary, I try to express myself as much as possible. Because, although the work may remain abstract, I believe that the imagination behind it should be understood sharply.

For example, more than 100 press members attended the press conference for the Guggenheim Bilbao, and there, almost everyone asked the same question. For the first time, in an art-focused press conference, we officially tried to talk about the most current problems of Europe in a way that is understandable, without looking down on them and equally. Of course, more than 10 articles that came out in response to this mostly said the same thing. We received very positive feedback. It was said that it brought transparency. By the way, I would like to suggest (American conceptual painter) Mark Rothko here. Because Rothko says, ‘My works are a space.’ I think the same way. Our works are a space, and when we go into that space, what people’s minds, souls, and thoughts encounter is important to me. Creating a safe space and being able to resolve the boundaries where the mind can be freed from fears—these could be delusions, privacy, ‘data,’ damage to nature—let’s think of a time when we can be free from all of these. What are we doing? Let’s say we solved these, because we can solve them: Right now, as humanity, we have technology in our hands. Where are we going with it? Talking about these things excites me tremendously.

Have you ever received partnership offers from institutions or individuals like Google or similar companies, or SpaceX, Elon Musk, etc., either during crisis periods or election processes for your projects?

Many, many offers have come. But I felt that there was something ‘discriminatory’ in each of them. I felt that a dream belonging to one place could not behave in varying degrees in another place. These were ideas that suggested I could ‘pontificate,’ but I didn’t want to ‘pontificate!’ My intention was to look at equally important issues for everyone, like nature. I don’t know of anything more important than nature, something that is equally important to everyone at the same time. When nature disappears and ends, nothing else will have any meaning. I couldn’t find a problem more ‘equal to everyone’ than nature, which is one of the most fundamental problems, the shared problems that form the basis of humanity, the very air we breathe. And I realized that everything else somehow, from one perspective, always creates another ‘duality.’ And if this is the life I live in this plane, I decided to spend the energy I will use not on dreams that separate, but on those that bring together, unite.

When talking about works or artists that have triggered you as role models in your understanding of production, you mentioned the minimalist conceptual contemporary painter Mark Rothko. At the same time, when I look at your works, the 1980s cult Artificial Intelligence film War Games also comes to mind. When you place your creative possibilities alongside diplomacy, are there any dreams you have built?

Actually, for the last four years, I have been working with a very valuable Amazon tribe called the Yawanawa. It’s approaching five years. I am a part of this. I have a name. They are not just any people. I have a very special bond. I am connected to them like family. I am someone who has understood and listened to their problems and, through them, the problems of the Amazon. And to solve these problems, but without speaking, to really be able to support solving them, to take action, to be able to act, last year we donated a series of artworks. And through these donations, the chief transparently presented six structures in the middle of the Amazon. One of them is a school, another is a museum, and the other is a cultural center. Last month, 400 people, who had never met before, from various tribes, sat together for the first time in the middle of the Amazon with 40 spiritual leaders, and they were able to talk about and discuss the world and life. This is one of the greatest impacts I have ever seen and discussed. I think when we consider this as ‘diplomacy,’ these 400 people were able to express their existence to the world peacefully and with good intentions. We achieved this. These people are 500, 600, 1000 people. Let’s remind again: These people are ‘very small,’ with no power we know of, but they are the best protectors of the world, unheard, far away, with no means. For us, they are the ‘ones who live in our lungs.’

As you know, ‘Esperanto,’ as a global language experiment focused on the UN, is remembered as an effort worked on in the 1950s but one that couldn’t have enough impact. If we consider that you’ve somewhat produced a ‘data language,’ do you have a dream for a common language that could be produced in the world?

Definitely, this is a very beautiful question! I truly and always say this from my heart. Truly, my dream is to find the language of humanity. But when I talk about this language, I’m not talking about the hundreds of languages, borders, or passports that we are currently using and have created. Do all cultures, nations, and countries have the possibility of having a new language thanks to Artificial Intelligence, whatever we call humanity? Does humanity have another language that we didn’t know, didn’t hear, or haven’t discovered before? For example, like nature, which we are still trying to understand, this living being that has existed for millions of years and with which we still can’t establish communication. We don’t have a language. We haven’t found the language of nature. Can Artificial Intelligence really show us the language of nature? If such a thing were to happen in this technological era we are living in, I think it would be meaningful for my feelings, dreams, and projects to somehow be a part of art. I don’t know if my lifetime will be enough. But, I can say that the intention of ‘data’ in my works is this.

Also, linguist, art critic, and academic Zeynep Sayın’s in-depth work in recent years, ‘Çizginin Boşluğu’ (The Space of the Line), which explores the languages and cultures of South American indigenous peoples, as well as the images and functions they produce, is currently on the shelves. In the book, it is explained that an Amazon tribe has a language called ‘kene,’ which has both physical and visual references, and evokes geometric and even semi-geometric abstract motifs found in computers. Could it be that the Amazon natives you’ve connected with also have a shared medical, cultural, and social language with nature?

“Actually, their songs, prayers, paintings are a kind of language for them. Of course, this is not a language in the sense we are used to. The works they create, the dreams, the music, the poems, and the experiments are a new language. But unfortunately, this has not been able to create a new memory like our publishing, academic, and information technologies. In the social minds of these people, as I said, a group of fewer than a thousand people has continuously been able to record and preserve this information, and the fact that the rubber barons stopped them for about 20 years in the late 1980s; all of this feels to me like this: There is a group of people in the Amazon who truly live with nature, who are in nature and have witnessed it, and who have understood nature for thousands of years. This is like an endless journey. Every time I go there, there is incredible wisdom. It’s so deep! Let’s put aside our hats that always look down on the other side of the world, the ones that are supposedly in control of technology, from our phones to our watches. This is a way of conversing with them and realizing how much we are lacking.