20.01.2025

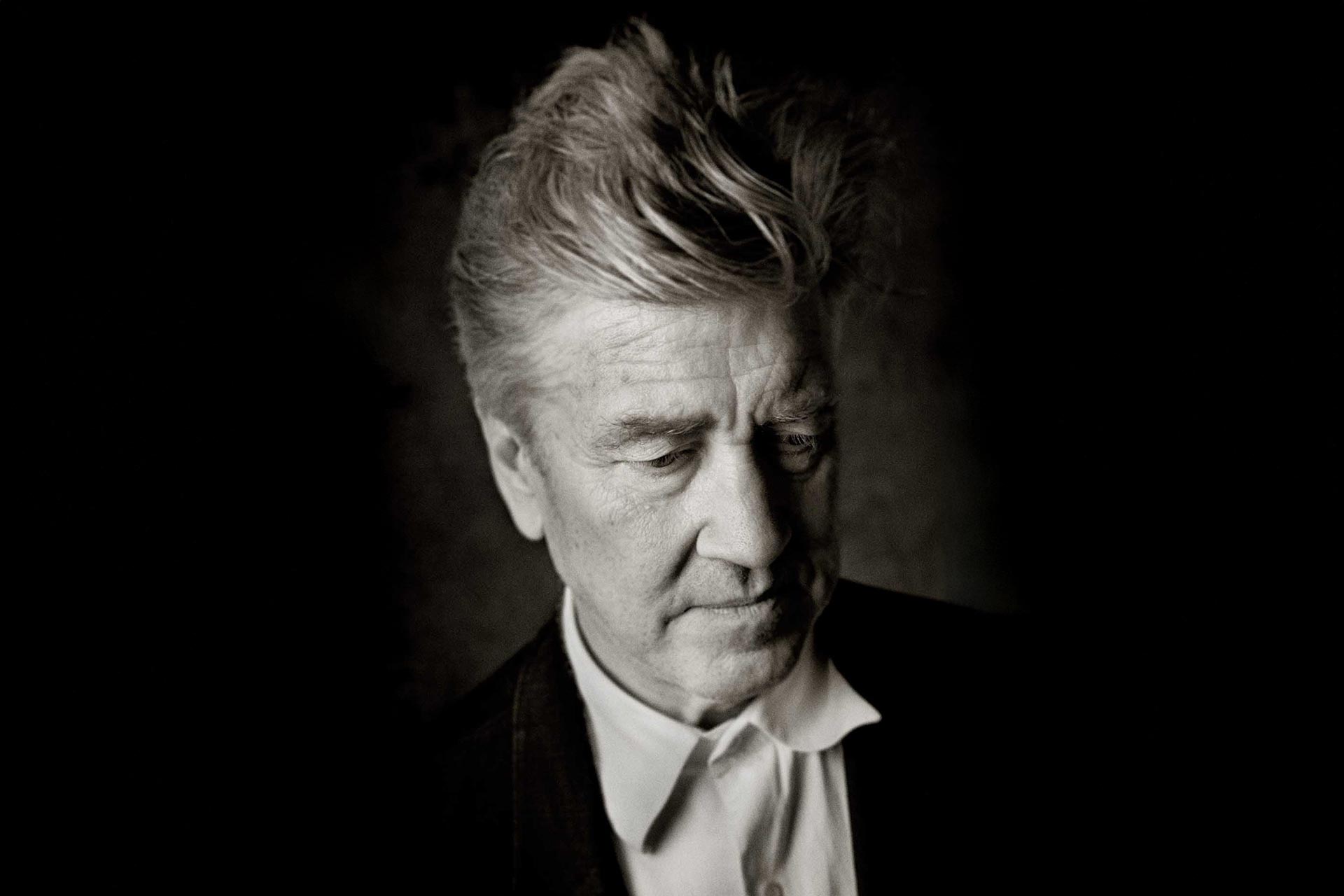

On January 16, 2025, David Lynch, the legendary filmmaker who passed away at the age of 78 in the United States, began his illustrious career more than fifty years ago with a foundation in fine arts. Over time, Lynch evolved into a masterful director, but he never silenced the many other voices within him: the actor, the musician, the painter, the sculptor, the designer, the writer, and the photographer. Awarded the Palme d’Or, Golden Lion, and César Awards, Lynch’s work drew inspiration not only from the idle souls of the mortal world but also left an indelible mark on it. Through his creations, he offered the world unparalleled opportunities to confront the Goliath within himself, leaving behind a legacy that transcends genres and disciplines.

It was a cold January evening in Istanbul, marked by time and the hour. The news first flashed across my pocket’s greedy screen via international CNN. Then, everyone knew: the tobacco enthusiast David Lynch, on January 16th, had passed away at the age of 78 in the United States, unable to endure the suffering caused by the illness he had been struggling with.

In response, I attempted to honor his ‘still’ (or rather, supposedly still) images, sculptures, and designs with this lengthy piece, the length of his Lost Highway (1990, Dir: David Lynch), though I may have done so out of ignorance.

How should I remember David Lynch, the American director, screenwriter, editor, writer, sculptor, designer, printmaker, and painter? I wasn’t sure. For Lynch’s truth was always ‘suspended in the air.’ It had a scent, but it could never be fully grasped. Lynch never asked for any sense of suspicion or emotional depth from others. Or perhaps he did—who knows? Of course… Lynch was everything that began with “Perhaps.”

He was the distance of visual and auditory journeys, created by the droplets of meaning emitted by the projection of cinema. Perhaps it was the olive of doubt, the absurd generosity, distilled by Lynch from figures like Marcel Duchamp, John Berger, Samuel Beckett, Guy Debord, Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Paul Sartre, or even Albert Camus—a cry, a charismatic, gray-feathered gaze that screamed to the world with every work of his.

Perhaps this is why, at the release of every Lynch film—each one as fleeting as a jazz “session”—people, without speaking a word, secretly envied one another, each holding the colors, sounds, and darknesses of Lynch’s work in their minds. But, perhaps out of the same selfishness, they couldn’t even share it with each other, afraid of tarnishing their own identities in the process.

Like competitive classmates who, even after an exam, don’t talk about their grades, right or wrong, we scattered, hoping that no one would “Lynch” us with our own foolishness.

David Lynch was born in 1946 in Missoula County, Montana, USA. It was as if his birthplace itself was a living set for his stories, but at the same time, it would remain a half-open air prison for his fate throughout his life.

Lynch, whose father worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, gathered his observations about humanity and life during his early wandering years. Moreover, Lynch was a post-World War II child. In a way, he came into the world, carrying the full violence inherited from his parents, his body caught between their compressed flesh and the hunger for sweat—bursting forth like popcorn, fresh and unique, each kernel carrying a heavy burden.

Perhaps this is why Lynch’s art always silenced us, hypnotized us, infiltrated us to our very core, leaving us with a melancholic, nauseating fragrance of films and popcorn that, when the credits rolled, sent us out of the theater, stunned, to face our shabby fates.

David Lynch was a child of the “Boom” generation. Had he lived to see January 20, 2025, perhaps he would have celebrated another year of life. He hadn’t forced it. Life was a bucket to him. Whether full or empty, life was just a bucket. A popcorn bucket. Or perhaps that enormous ashtray from his childhood that we never managed to crush, the one that ultimately led to his death.

Lynch, since 1990, has been the one to most powerfully and profoundly provoke discomfort and doubt in me.

For instance, there was his three-season, 32-episode Twin Peaks TV series (1990–2017), which first aired on ABC in the U.S. and, due to the so-called “First Gulf War,” delayed its broadcast even while we watched it live with Peter Arnett on CNN. This was Lynch’s first television production.

Twin Peaks. That show, which aired on Türkiye’s first private channel, ‘Sihirli Kutu’ / Magic Box—Star 1, and perhaps during those Sunday late-night hours—captured our curiosity and hunger for ‘other worlds.’ Its melancholic theme music, composed by Angelo Badalamenti, became the national anthem of melancholy. We even bought the cassette, a symbol of rebelliousness, as if in a trance. Tiny spaces gave birth to enormous human stories, unfolding one after another.

It was as if those who watched the show were part of a cult, but everyone promised to watch it while secretly hoarding their own numerous secrets. We even knew that some of our elders, with their Betamax and VHS video recorders, mystically recorded the dubbed episodes during the TV broadcasts, treating them like cherished heirlooms. Yet, curiously, we could never access all of those tapes at once. The original soundtrack of Twin Peaks (which Lynch turned into a film in 2006 titled Fire Walk with Me) was like a forbidden treasure. For some reason, it was either kept at a distance from others or played only when alone, the hidden background music of our adolescent dreams, constantly being played on the cassette or CD players of our own fates.

Perhaps that generative discomfort began right there: I remember thinking I understood what it meant to craft life with ‘closed eyes,’ to manipulate subtly, while actually ‘having done it without doing it.’ I remember thinking, “I thought I understood that I thought I understood that I understood it” (and it goes on like that…).

Because, as the album endlessly repeated itself, I would keep closing my eyes to the same thing, but insistently turning a blind eye to different interpretations and forms, indulging in both pleasure and sadness.

What was the core allure of the manic-depressive joy that David Lynch left in people?

Perhaps it was this: Maybe Lynch, too, was eager to carry the ‘Post-Modern’ label—something that could be considered a kind of rally for the side effects that had jumped from his life into his identity, a term perfectly suited to the American reality. He dedicated it to his own helplessness, like a filigree, carrying it with all of us at once.

However, for Lynch, Post-Modernism, cunningly embedded in his body of work as an ‘Ex-Libris,’ had already entered the academic and cultural world long before I turned 15. It wasn’t new at all. The first to incorporate it into his mouth and pen was the French philosopher Jean François Lyotard in 1979.

Later, Lynch introduced us to the addictive legacy of German expressionism through ‘Film Noir.’ Crime, punishment, provocation, destiny, betrayal, forgiveness… Following Lynch’s frames, which had a mass psychotherapy effect, was enough to explore them all simultaneously.

Perhaps now, it’s time to focus on the ‘objects’ and origins Lynch left behind, to dissect the attic of meaning he created, even through official publications:

Let’s look at the archives (1): According to data we received from Pace Art Gallery in New York, with whom Lynch collaborated and held his only exhibition in 2022, Lynch studied painting at the Boston Museum School and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in the late 1960s.

Furthermore, his early experiences at the American Film Institute Archives played a significant role in shaping his artistic identity and in leading to his first film Eraserhead (1977). In this period, Lynch also designed his first ‘moving painting,’ Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) (1967), a multidimensional composition under a moving projection. This multimedia work was considered Lynch’s ‘first step’ into video and filmmaking. In fact, he even earned a scholarship with this project.

Perhaps, this was also a reflection, in a global, anarchic, and avant-garde way, of the collective narrative revolution made by numerous artists—like Nam-June Paik, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, Joseph Beuys, Joseph Kosuth, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Chuck Close—who, through installation, performance, and video art, turned the inside of image, history, and the sacred outward.

Maybe, through this creation, humanity, in those years, was trying to subversively infect the very capitalist and property-driven industry it had become addicted to. With all its anxiety, it attempted, like a microbe, to destroy and/or redeem it from the inside out.

And some, by claiming this in art history, tried to leash it with terms like patronage, craftsmanship, creativity, or thought leadership, narcissistically applauding themselves and stopping there.

Those years were also when the cries of ‘Independent’ theater, cinema, performance, and plastic arts echoed loudly, one after another, against the art of capitalism or authority in both the world and the U.S. In New York, LaMaMa, Sundance Film Festival, in New York again, The Factory, or Apocalypse Now with Coppola—things really heated up.

Perhaps Lynch, too, in his works, wanted to hold onto the hand of this idle, parentless truth that hung in the air. Lynch, with his never-ending doubt, always held onto the ‘found objects’ he created through a collaborative creative act directed at humanity and life. In his films, it seemed as if he was at times greeting the melancholic, platonic, guilt-ridden erotic existence of modern American painter Edward Hopper, British director Alfred Hitchcock, existentialist Alain Resnais, or Jean-Luc Godard. Perhaps this was where it all began.

Maybe, the eternal, inevitable being called ‘the feminine’ was rendered into a solemn tribute and elegy in all of his films. Yet, with every showing, regardless of whether you were male or female, they were immediately accessible, welcoming you into a world full of respect. Lynch did not choose to be a god. He did not embrace descending from above with his films. The danger, perhaps, was the divine, forbidden eroticism of heaven, whose promotion was done through illicit actions—this was likely the true fragrance of his works. His creations smelled like dark, unsweetened, fiery coffee—a kind of human ‘detritus’ stripped of sweetness, full of clarity.

Perhaps David Lynch, in his works, always presented a kind of ‘live autopsy’ experience. The so-called exclusive delicatessen privilege of accessing his films, perhaps, stemmed from this.

Lynch may have been sanctified for continuously capturing the marginalized individuals and stories that had failed in life—their shared struggles, whether dead or alive—by stacking up images in the truth market where images turn into capital. The artist repeatedly made objections and, if necessary, rehabilitated all those ‘illegitimate’ states and personalities in the wake of World War II, particularly within the vast lie of the United States. By recognizing them, he either sanctified or legitimized the losers in their faults or sacrifices.

Yes, Lynch was brave. Without ever denying that the devil could also be an angel, he played with it in various forms in his films. He spat his doubts out through his creativity and rule-breaking, relentlessly rejecting everything that was handed to him in the ‘entertainment’ industry, rubbing it against the ‘three-dimensional’ human characters he made—both the good and the bad.

Perhaps Lynch, with the nausea gray and smoke-infused texture of his works, continued to add the European, surrealistic, ‘Brut’ / Total, existential, nihilistic spices from the visual arts (history) and his training, both verbally and effectively, without ever stopping.

The artist, in his works spanning across visual arts, TV, photography, and cinema, earned his freedom and originality until the very end through the personal forms and images he created, which were born from his courageous fairness toward both life and death. With a darkly humorous tolerance for the absurdities of mortal existence, he gave his all, searching for himself in what was not himself, and in the simple pleasure of seeking, he realized the ‘now’ with a childlike carefreeness and an enviable truth.

Should we look at the abstract figures of life he presented in his 2002 “Big Bongo Night” exhibition at Pace Gallery—initially seeming like “stick figures” or “burnt matches”—through this same lens of feeling, as a possible tribute to Afro-Americans, the true intellectuals of the United States? In these artworks, much like in Lynch’s films, the “total nothingness”—or in today’s trendy term, the “Lonely Crowd”—seems to catch my attention once more. Through his melancholic productivity, drawn from the darkest and most fleeting moments, Lynch could effortlessly generate a life perspective nourished by twilight, reflecting respect for each ‘being’ that arose in the present.

These designs, each seemingly hanging as a skeletal memory, perhaps represent Lynch’s closest circles, mysterious individuals who have unknowingly crossed into his world. Every one of these “lightbulb heads” likely offers a personal on-off point for actions that belong to them.

Interestingly, in his oil paintings on wood and canvas, Lynch also sacrifices the same murky, unsettling ‘space’ for the compositions he creates. Whispered handwritten scrawls hanging in the air, discarded Earth formulas spilling from the canvas in an instant, limbs, objects, or individuals falling from the image—these are singular moments that seem to catch the air with a freedom that can only be envied in dreams.

Lynch’s paintings, corresponding to all of these moments, produce active thresholds for each other. With his work, David Lynch expels both the depression of being caught and the Munch-like deafening freedom of those who have fled from themselves, with the final visual resonance of a justified hum and ringing.

Perhaps, in these works, which are certainly not inclined toward reconciliation with reason, sympathy, or any form of analysis, the distinctness of the images emerges from nothing but the independent peace Lynch has granted them.

Through his personal modes of expression, brewed from existential anxiety, Lynch demonstrates that he never plagiarized. The artist perhaps deserves to be remembered as a ‘troubled’ person more than anything. Lynch has consistently shown us how this world, constantly copying from the lie of ‘nothingness,’ has been proven with the deathless bounty of his suffering, according to the level of his own ‘misery.’

Maybe Lynch, even before artificial intelligence existed, would say “The situation was clear from the beginning.” All the copies were around, and they were all chaotic.

(So, how should we link David Lynch’s art with Türkiye here? Forgive my ignorance, but when I think about Lynch’s art, the first names that come to my mind, along with the unique and transcendent worlds they introduced us to, are Yüksel Arslan, Cihat Burak, Nevhiz Tanyeli, Mübin Orhon, Neş’e Erdok, Fikret Muallâ, and particularly Mehmet Nâzım, Sarkis, Komet, and Mehmet Güleryüz. Perhaps, many artists in Türkiye, who are trying to break through the formalities imposed on creativity, cutting their own navel with their brushes and whatever material they have, are, in a sense, mentally and sentimentally connected with Lynch.

Perhaps, this “view cast upon the world,” in today’s material and conceptual reflexes, could be embodied by artists such as Aret Gıcır, Leylâ Gediz, Çağrı Saray, Hakan Gürsoytrak, Yaşam Şaşmazer, Selim Birsel, Cem Dinlenmiş, Nazif Topçuoğlu, Zeyno Pekünlü, Cem Dinlenmiş, Mert Öztekin, Kerem Ozan Bayraktar, and the late Mehmet Gün, among others—whether knowingly or unknowingly. This may be something to consider.)

Anyway, without leaving the Lost Highway, let’s return to the personal and fruitful history of the eternal “Film Noir” screenplay Lynch has written on our foreheads, through official records:

The artist has already been celebrated at numerous prestigious contemporary culture and art institutions during his lifetime, including exhibitions such as “Air is on Fire: 40 Years of Paintings, Photographs, Drawings, Experimental Films, and Sound Creations” (Fondation Cartier, Paris, France, 2007), La Triennale di Milano, Milan, Italy (2008), Ekaterina Cultural Foundation, Moscow (2009), and GL Strand, Copenhagen, Denmark (2011).

Of course, Lynch’s photography, which is hardly even worth mentioning, has also made headlines, with events such as “The Factory Photographs” at “The Photographers’ Gallery” in London in 2014, and “Squeaky Flies in the Mud” at Sperone Westwater in New York in 2019. Lynch also continued to expand his list with exhibitions like “My Head is Disconnected” at HOME in Manchester in 2019, and “From the Fringes of the Mind” in Tokyo the same year. Additionally, the retrospective “Someone is in My House” at the Bonnefantenmuseum in Maastricht, Netherlands (2018-19), or “Between Two Worlds” at the Queensland Art Gallery in Brisbane, Australia (2015), are valuable clues for us not to forget Lynch, who was applauded at Fondation Cartier Paris in 2007.

Moreover, it’s worth mentioning that the artist, who has also received recognition for his musical work and had a professional collaboration with David Bowie, had a unique academic survey/research dedicated to him in 2014 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, where he had previously studied.

To conclude, the officials at the PACE Gallery in New York, upon Lynch’s passing, emphasized in their statement that, over a period of more than half a century, Lynch nourished a ‘multi-disciplinary’ production practice rooted in his early years as a painter.

There’s no harm in repetition: The artist, who dedicated himself to many different mediums including drawing, photography, printmaking, sculpture, music, and film, is still remembered for his contributions to cinema, which can be considered a bouquet of all these arts, through works such as Eraserhead (1977), The Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), Twin Peaks – Fire Walk With Me (1991), Lost Highway (1997), Mulholland Drive (2001), and Inland Empire (2006).

In 2020, Lynch was awarded the Honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement and had been nominated multiple times for Best Director, Screenplay, and Adapted Screenplay Oscars. His paintings, much like his films, are decoded by Pace Gallery in the following way:

These works “often focus on moments of decay in domestic, everyday settings. Filled with unease, these works are loaded with threatening, mysterious images.” As the gallery also highlights, “Drawing from the visual languages of Surrealism and Art Brut, Lynch embraces forms that may seem ‘crazy’ to ‘normal’ people, using media, perspectives, slanted planes, and ‘skewed’ narratives and viewpoints as his tools.”

Pace Gallery officials emphasize that Lynch “explored the animations of physical and industrial decay,” and at the core of all of this, generally focused on American life, addressing “a widespread sense of unease that resonates with the dark realities of today.”

Indeed, the gallery’s CEO, Marc Glimcher, sanctifies this legacy and bids farewell to the artist as he journeys towards the white screen of eternity with the following words:

“Anyone lucky enough to grow up in Lynch’s early years had the mental architecture of the 1980s and 1990s. The ‘mind(s)’ were largely rebuilt by his genius. This is an incredible loss for us, for a pure creator. He was the man who turned madness into philosophy.”

With this article, I tried to speak about David Lynch, the man who lived in Los Angeles, the one who, like all of us, fell into the world scattered across life.

David Lynch, the recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Oscar, has become an increasingly valuable director over time. He never silenced the actor, musician, painter, sculptor, designer, writer, and photographer within him. Winning the Golden Palm, Golden Lion, and César Awards, David Lynch left an unparalleled mark on the world, offering every possibility in his works to deal with the Goliath inside him, inspiring us human wanderers of the fleeting world.

Lynch, just like in his personal Paris exhibition where he only produced a limited-edition 2000 album, when he writes “The Air is Burning” with his eerie handwriting, even as he declares the scattered, the eternal absurdity, he was right again, even when he left.

He left behind his incredible, immense ghost, which had fallen into a dead grayness like Cinderella in the City of Angels, with whom he could never break free of the constant battles.

Perhaps, he was the one who, with the avant-garde responsibility, threw the first and last cigarette butt into this world, which terrified all of us. But no one ever imagined that his warnings would turn out to be so real.

Perhaps, David, the true Goliath, was the one who never left his own side.

All sources and visuals:

———————————-

- David Lynch, “Big Bongo Night” adlı kişisel sergisi, 4 Kasım, 17 Ekim 2022, Pace Gallery, New York, ABD sergisi yayını ve sanatçı adına basın ve kamuoyu için yayımlanan özel taziye bülteni, Galerinin İzniyle.

- “Varoluşçuluk ve Yeni Kara Film: David Lynch Örneği”, Deniz Tansel, T.C. Ankara Üniv. Sosyal Bilimler Ens. Radyo TV ve Sinema Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi, 2007