The White House Art Collection, which added just seven new pieces during the first term of the U.S.’s “wealthiest” President, Donald J. Trump, holds a rich and fascinating history. While the collection became more diverse during the Clinton and Obama administrations, the Republican Bush family took a particular interest in African American art. Through a combination of donated and purchased works, the collection has continuously shaped and reflected the evolving identity and spirit of the White House.

As we know, we are in a time when the Republican Party—symbolized by the “Elephants” (conservatives)—has won a fiercely contested 2024 Presidential election against the Democratic Party’s “Donkeys.”

The 45th President of the U.S., the sensational real estate mogul, businessman, and media personality Donald J. Trump, is preparing to return to the White House in Washington D.C. following his inauguration on January 6, 2025, for his second term as the 47th President.

However, the walls (and archives) of the White House are never lacking in cultural and artistic competition. This constant vibrancy can be traced back to a law passed by the U.S. Congress in 1961, during the presidency of John F. Kennedy, the Democratic leader who was tragically assassinated on November 22, 1963, while heading to a campaign rally in Dallas.

This law established that the collection of art in the White House would be treated as part of a “permanent collection,” created by the “White House Historical Association.” The artworks are managed as a museum under the “State Rooms” of the White House, with support from the newly created “Curatorial Office.”

Over time, the White House Art Collection has grown to include a wide range of works, from traditional landscapes and historical portraits to modern and contemporary art, as well as outdoor sculptures and installations.

The prestigious works donated to the White House have ranged from the late 1940s to the present day, with a timeline and stylistic diversity stretching from the 1800s to the late 1930s.

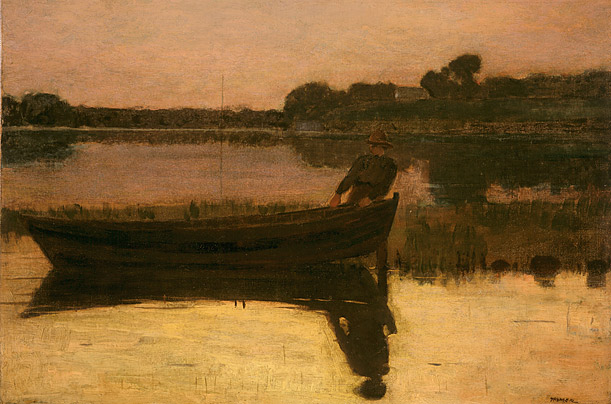

The permanent collection includes works by notable artists such as Michele Felice Cornè (1752-1845), Thomas Birch (1779-1851), George Cooke (1793-1849), William M. Hart (1823-1894), George Henry Durrie (1820-1863), Ferdinand Richardt (1819-1895), Worthington Whittredge (1820-1910), Martin Johnson Heade (1819-1904), George Inness (1825-1894), Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), and many others. These works represent classic landscapes, figure studies, and respected portraits, all of which continue to add to the historical and artistic significance of the White House.

The White House’s ‘In-House’ Curators: Presidents and First Ladies

In essence, each U.S. President and their family can be seen as the “in-house” curators of the White House during their time in office. By adding artworks that reflect their personal tastes and worldviews, they become both the creators and the products of the collection’s rich legacy. Within this context, some Presidents focus on showcasing American artists, while others may choose international artists whose work references the country’s ethnic diversity or serves as a form of cultural diplomacy.

Furthermore, as a building that often has “the world’s eye upon it,” the White House can also act as a public symbol, leaving a catalog-like imprint on the nation’s cultural and political identity. Culture and the arts, as is well known, play a key role in the U.S.’s broader narrative of freedom and democracy. In fact, some art historians and journalists argue that the promotion of Abstract Expressionism, an art movement that emerged as a challenge to the Soviet Union’s cultural policies, was part of a larger global campaign supported by the U.S. government. Reports even suggest that the CIA was involved in facilitating these efforts through international exhibitions.

The White House collection includes nearly 70,000 objects, ranging from kitchenware and glass to around 500 paintings. When a new President is inaugurated, the White House curator’s office selects new works to be displayed in public spaces, including the West Wing.

Both the President and First Lady have the opportunity to select pieces from the existing collection, or they may borrow works from other museums. Alternatively, the First Family can send someone they trust to various museums to choose pieces for their private quarters.

Jacqueline Kennedy’s Influence on the Collection’s Destiny

To focus on the origins of this invaluable collection, it’s clear that the way art was acquired for the White House was largely shaped by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy in 1961. After President John F. Kennedy took office on January 20, 1961, and the White House became their home, Jackie took on the task of revitalizing rooms that she felt lacked inspiration.

The Kennedys were already well-established as art collectors with a strong understanding of art history before moving into the White House. Their commitment to culture and the arts was publicly demonstrated when they hosted a dinner at the White House, attended by prominent modern artists like Mark Rothko, Franz Kline, Andrew Wyeth, as well as literary figures such as Saul Bellow and Tennessee Williams.

As a result of this prestigious event, President Kennedy and Jacqueline succeeded in establishing a connection with the French Minister of Culture, who allowed the Mona Lisa—one of France’s most famous national treasures—to be exhibited at both the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the National Gallery in Washington, D.C., for a year starting in December 1962.

In her first year as First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy devoted much of her time to sourcing works of art, antiques, and paintings that she felt would accurately represent American history and culture. This led to the creation of the Fine Arts Committee in 1961, a major initiative that sparked a large-scale restoration project in the White House. The committee brought together experts in American historical decoration and conservation to oversee the development and expansion of the White House’s art collection.

The ‘White Rule’: ‘Works Cannot Be Kept by the President’

As the White House collection expanded, Mrs. Kennedy and the Fine Arts Committee realized they needed someone to organize and manage the growing collection. This led to the creation of the position of White House Curator, and Lorraine Waxman Pearce was appointed as the first curator.

Not long after, in September, Congress passed Public Law 87-286, formally designating the White House as a museum and recognizing Mrs. Kennedy’s efforts as part of a historic preservation initiative. This law safeguarded the donated works, with a clear stipulation: items in the collection could not be personally kept by any sitting President. Instead, they would be cataloged and preserved as part of the public collection, leading to the establishment of the White House Historical Association on November 3, 1961.

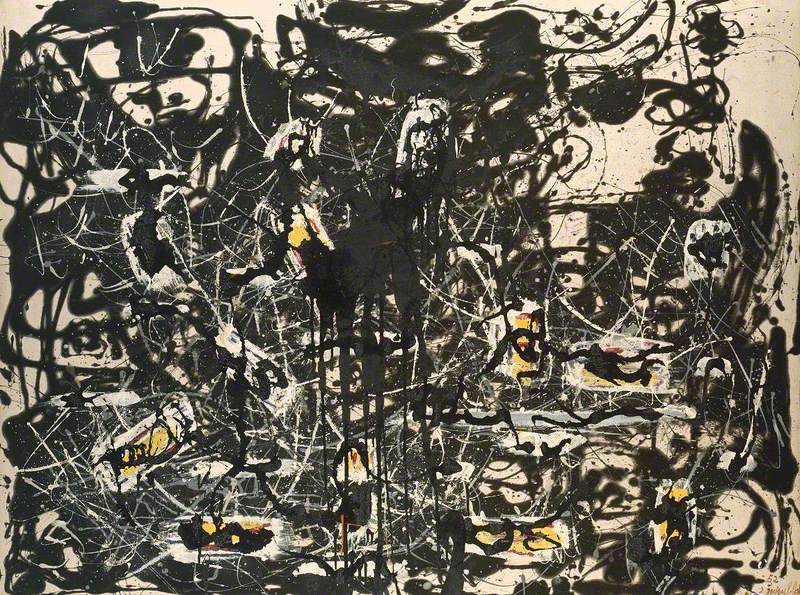

Looking at the early additions to the collection, we see works such as Cathedral (1947), an abstract piece by Abstract Expressionist pioneer Jackson Pollock. It was sent to the White House by the White House Art Festival Foundation and was added to the collection in 1967, during President Lyndon Johnson’s administration, courtesy of the Dallas Museum of Art.

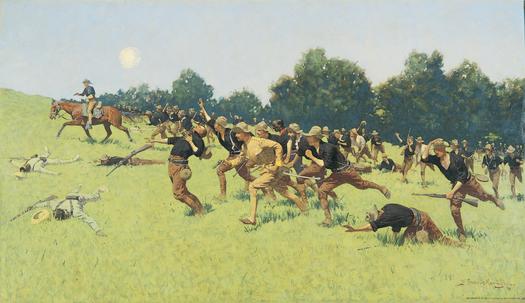

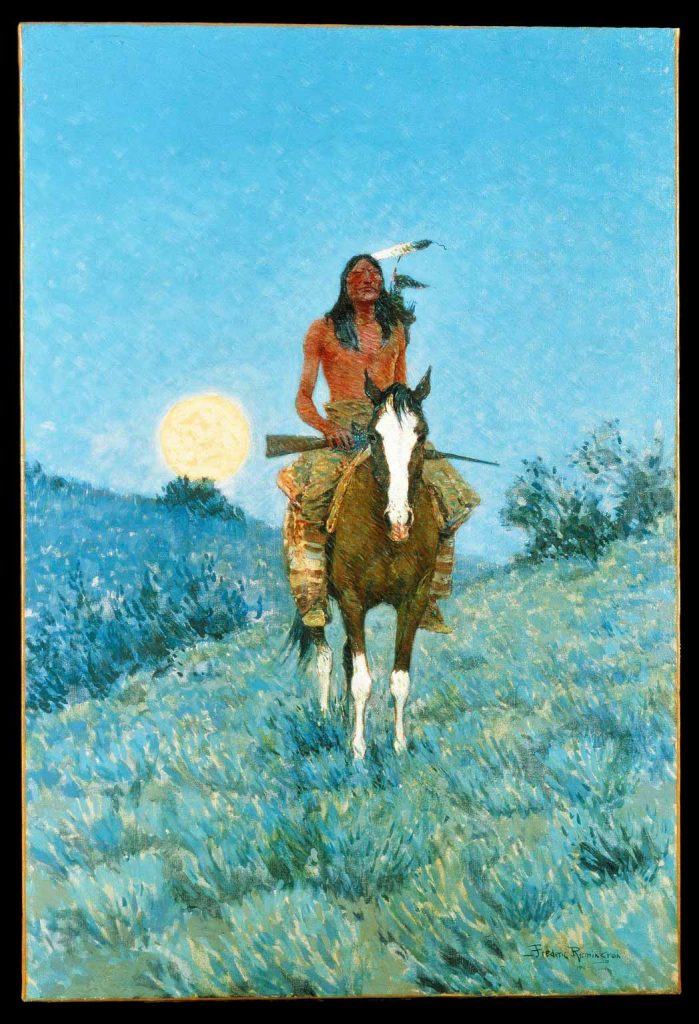

A couple of years later, under President Richard Nixon, the White House borrowed The Charge of the Immortal Cavalry at San Juan Hill (1898) by Frederic Remington from the Frederic Remington Art Museum for display in the Roosevelt Room. Remington’s influence continued: his sculpture Rebel (1909) was loaned to the White House by the Brooklyn Museum during the Clinton administration, and it was displayed in the West Wing Reception Room from 1996 to 2010.

A Growing Interest in Modern and Contemporary Art

The White House’s engagement with modern art dates back decades. One notable acquisition was Georgia O’Keeffe’s New Mexico – Bear Lake (1930), an early expressionist landscape rich in psychological and social meaning. First Lady Hillary Clinton purchased the painting from a New York gallery in 1993, and it was placed in the White House’s Green Room before being relocated to the White House Library.

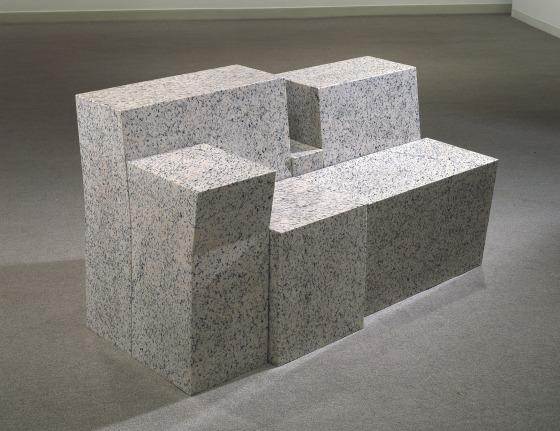

Similarly, sculptor George Segal’s Walking Man (1988) was loaned to the White House by the Walker Art Center for the 1994-1996 exhibition 20th Century American Sculpture at the White House, where it was displayed in the First Lady’s Garden. Another piece featured in this exhibition was Scott Burton’s Granite Settee (1982-1983), an abstract work that was loaned from the Dallas Museum of Art and displayed at the White House during the same period.

The Clintons also brought The Lantern Door, a striking painting by realist John Frederick Peto, into the White House from the Brooklyn Museum. The piece was hung in the West Wing Reception Room, where it was shared with visitors and dignitaries.

The White House’s Most ‘Active’ Collection Period: The Obama Years

The White House experienced its most active period of art collecting and display during the two terms of President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama. According to the New York Historical Society and Library, at President Obama’s first State Dinner, the painting View of Yosemite Valley (1865) by Thomas Hill caught the attention of many, while the White House collection itself was distinguished by the generosity of its donors.

From 2009 to 2017, the Obama family added modern and contemporary pieces to the White House, further enhancing the collection. Among the new works was Early Bloomer, a painting by Robert Rauschenberg, donated by the Rauschenberg Foundation. First Lady Michelle Obama also made her own mark, introducing works by contemporary artists such as Ed Ruscha, whose I Think I’ll… (1983) was placed in the private rooms during the early years of their administration.

During their time in office, the Obamas took a groundbreaking step in diversifying the White House collection. They called on museums, galleries, and private collectors across the country to lend works by African American, Asian, Hispanic, and female artists. This effort not only added fresh voices to the collection but also reflected the nation’s growing cultural diversity. Notable works included pieces by African American artists like Alma Thomas, William Johnson, and Glenn Ligon, all of whom made their way into the White House collection.

In an even more significant move, the Obamas became the first First Family to display original works by Native American artists in the Oval Office, further cementing their commitment to broadening the artistic representation in the White House and reflecting the full spectrum of American culture.

Icons of American Art History in the Oval Office

The White House is home to an impressive collection of works by some of the most celebrated American artists. Among the many pieces displayed are works by Alma Thomas, Richard Diebenkorn, Jasper Johns, Mark Rothko, Norman Rockwell, and Edward Hopper. Over time, the collection has also expanded to include internationally recognized figures like Jacob Lawrence, Susan Rothenberg, W. H. D. Koerner, and Wassily Kandinsky. In this way, the White House not only serves as the residence of the president but also as a living museum. Every work donated to the collection becomes part of the institution’s permanent holdings, and some are even sent to the Smithsonian for academic preservation and study.

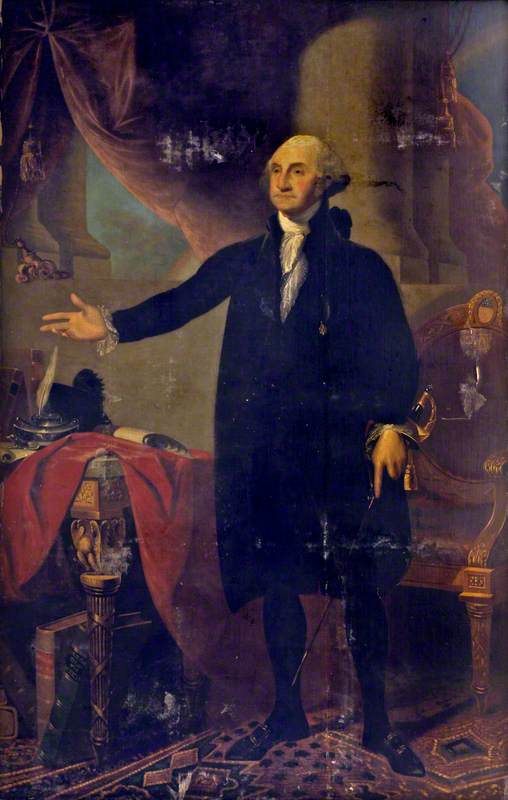

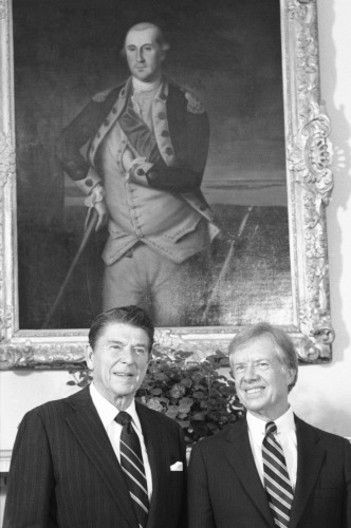

For those wondering which piece could be considered the White House’s equivalent of the Mona Lisa, the most iconic work is undoubtedly the famous portrait of George Washington. This portrait, depicting the first president at age 64 in his third presidential pose, has become one of the most recognized images in American history. However, what many may not know is that this painting is not the original. Despite this, its widespread popularity has made it a unique symbol. During the War of 1812, First Lady Dolley Madison managed to save the portrait when British forces set the White House on fire in 1814. In a dramatic escape, she quickly removed the painting from its frame and saved it from the flames. The original, painted by Gilbert Stuart, was later housed in the collection of British Prime Minister the Marquis of Lansdowne before eventually finding its home in the Smithsonian archives. Nevertheless, the copy saved by Dolley Madison holds its own special place in history. If you look closely, the portrait even features a visible copy of the Constitution and Laws of the United States, complete with a few minor typographical errors, adding another layer of authenticity to this enduring symbol.

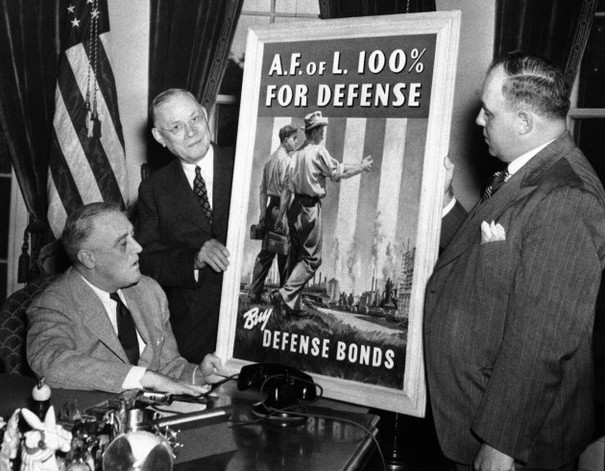

Another notable artist featured in the White House collection is the early 19th-century British symbolist painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts. Watts’ painting Love and Life caught the attention of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who had it prominently displayed in the White House. Many years later, this painting served as the inspiration for the visual theme of Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign, with the now-famous Hope poster. The original painting, which is housed at Buckingham Palace in London, was temporarily lent to the United States during Obama’s visit, adding even greater symbolic significance to both the artwork and the artist.

Along with these prominent works, the White House collection includes masterpieces by other influential artists such as Paul Cézanne, Vincent van Gogh, Winslow Homer, and John Singer Sargent. Each of these works contributes to the cultural and symbolic richness of the White House collection, highlighting the evolving landscape of American art while underscoring the importance of the White House as a guardian of the nation’s artistic legacy.

A Bold Critique of the Collection

Yet, a recent, comprehensive analysis of the White House art collection, published on September 27, 2023, by journalist and researcher John James Anderson (https://dcist.com/story/23/09/27/white-house-art-collection-diversity-issue-artists-modern-contemporary-art/), highlights significant issues facing the collection. Anderson points out that the White House Preservation Committee, which met on September 6, 2023, is encountering serious challenges. According to figures from the White House History Association’s book Art in the White House, of the 512 artworks in the White House collection, only 32 are by women, and just 12 are by non-white artists.

Looking at the historical growth of the collection, we see that after Jacqueline Kennedy established the position of curator in 1961, the collection grew substantially, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s. In that period, the collection nearly tripled, expanding from 119 works to 394. In 1995, the Clintons made a landmark acquisition, purchasing the first work by an African American artist—a seascape titled Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City by Henry Ossawa Tanner. The Clintons also commissioned the first official presidential portraits by an African American artist, Simmie Knox.

Following this, the Bush administration, known for its conservative stance, made notable strides toward diversifying the collection. They purchased a landscape by African American artist Edward Mitchell Banister and commissioned works from Asian American artist Zhen-Huan Lu. The Bushes also worked with the White House Historical Association to acquire The Builders by Jacob Lawrence, a powerful depiction of African American history and working-class life. At $2.5 million, The Builders remains the most expensive artwork ever purchased for the White House collection.

Despite these efforts, John Wilmerding, an art historian and the longest-serving member of the committee, admits, “I can’t say the collection is complete,” acknowledging that space limitations have made it difficult to keep expanding. While the collection is undoubtedly significant, Wilmerding believes there’s much more to be done. Anderson further critiques the current policies at the White House, stating that these policies make it difficult to incorporate more contemporary styles and artists from diverse backgrounds. “Many of the White House’s current policies make it harder to select contemporary artists and works by people of color,” he writes. He highlights the fact that unless a work is commissioned, such as a portrait or a holiday card, the White House tends to avoid acquiring works by living artists or those under the age of 25. Furthermore, materials like photographs and works on paper are often excluded from the collection due to their light sensitivity. The collection’s focus also remains largely on “leading” American artists, a problematic term given the art world’s history of excluding women and non-white artists.

Professor Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, an art history professor at the University of Pennsylvania and the first African American to earn a PhD in Art History from Stanford University in 2000, shares her insights, noting that the slow pace of diversification in the art world is widely recognized. She adds that the underrepresentation of women and people of color in the White House collection is not surprising, as it mirrors trends seen in many other collections. “I don’t think it’s unusual that women and people of color are underrepresented in the White House collection—this is something you see in many collections across the country,” Shaw states.

Anderson’s research also reveals a slowing rate of acquisitions over the years. For instance, President Richard Nixon added over 70 works to the White House collection, while President Ronald Reagan added 35, and the Clintons added 25. By contrast, President Obama’s administration saw the slowest pace of acquisitions, with only 12 works added. Anderson points out that this was the smallest increase since the Eisenhower era. Under President Trump, only six works were added, maintaining Obama’s slower pace.

These findings paint a picture of the White House’s evolving art collection—one that, while rich in history, still has much work to do in terms of diversity and inclusion. Looking ahead, we can’t help but wonder what art will find its way onto the White House walls during Donald J. Trump’s presidency, Trump himself having famously proclaimed “Make America Great Again. Will he choose to continue the trend of prioritizing traditional, often exclusive, art, or will his administration embrace a more inclusive and diverse vision for the collection? Only time will tell.