In the history of art, fatherhood, parenthood or filiation has been an inexhaustible source of research and observation. Featuring in the works of Michelangelo, Picasso, Albrecht Durer, Peter Paul Rubens, Cornelis de Vos, Rembrandt, Paul Cezanne, Jean-Leon Gerome, Edgar Degas, as well as Frida Kahlo, Louise Bourgeois and David Hockney, it seems like this topic has never lost its popularity.

Picture. It must be a strange mirrored bazaar that one picks out from among all the pictures whose name one generalizes under the concept “life”, sometimes knowingly and sometimes by keeping it a secret even to oneself.

When we talk about how painting is a measure of personality and a site of confrontation for artists on the occasion of the upcoming “Father’s Day”, the topic asserts itself as having a very active and serious aspect, especially in classical and modern plastic arts. Featuring in the paintings of Michelangelo, Picasso, Albrecht Durer, Peter Paul Rubens, Cornelis de Vos, Rembrandt, Paul Cezanne, Jean-Leon Gerome, Edgar Degas, as well as Frida Kahlo, Louise Bourgeois and David Hockney if one were to make a rough chronological timeline of art history, the topic seems to have never lost its popularity, whether it be in terms of parenthood or in filiation.

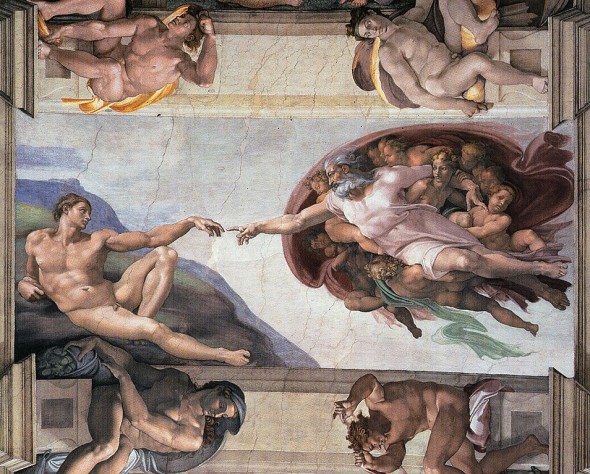

When we approach this quite obvious, fruitful topic in a more general way and try to look back on it, one of the symbolic and iconic works reflecting the relationship between religion and art, a Renaissance masterpiece, the fresco painting, Creation of Adam by Michelangelo Buonarroti, comes to mind. The master Michelangelo, who depicted the meeting of Adam and the Supreme God in heaven with an epic-illusory approach, doing full justice to the holiness of the occasion, is conducive to both an optical truth and a spiritual consistency by placing his masterpiece on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. It is a cult masterpiece in terms of respect and devotion to God. Despite the illustration of his strong and keen body in the gloom of his youth, Adam is sexually depicted quite innocent, in submission, in the garden of Eden, inferior and impotent in the face of God. While the work reveals the adventure of existence of intimacy within a distance of a finger between the son and father, God, who appears with angels, houris and servants around Him, comes down from His own ‘level’, reaches towards His son in His original form, embraces him and blesses him at an infinite level with His love and power.

Colour theory expert, painter Paul Cezanne’s portrait The Artist’s Father, Reading L’Événement stands out as an autobiographical and narrative treasure chest. Having completed this masterpiece, included in the collection of The National Gallery in Washington, USA, in 1866, Cezanne depicts his father, who did not approve of his profession, holding a paper, nodding to his old friend, famous writer Emile Zola, who became an art critic for the same paper in the same year. Likewise, Cezanne’s banker father, Louise-Augustine, never approves of the artist’s career choice in painting. In his masterpiece, Cezanne almost visually proves the distant relationship between him and his father. While his father, who experiences loneliness as seated in a cold, throne-like chair, wraps himself up in his own realm buried in the pages of a newspaper, the watcher – son – the follower tests him over and over again through his watchful gaze upon him at the level of the psychological full-length mirror he has placed. Moreover, behind his father, a still-life painting, probably referring to the creativity of the artist, almost ‘watches the back’ with all its stubbornness and efficiency.

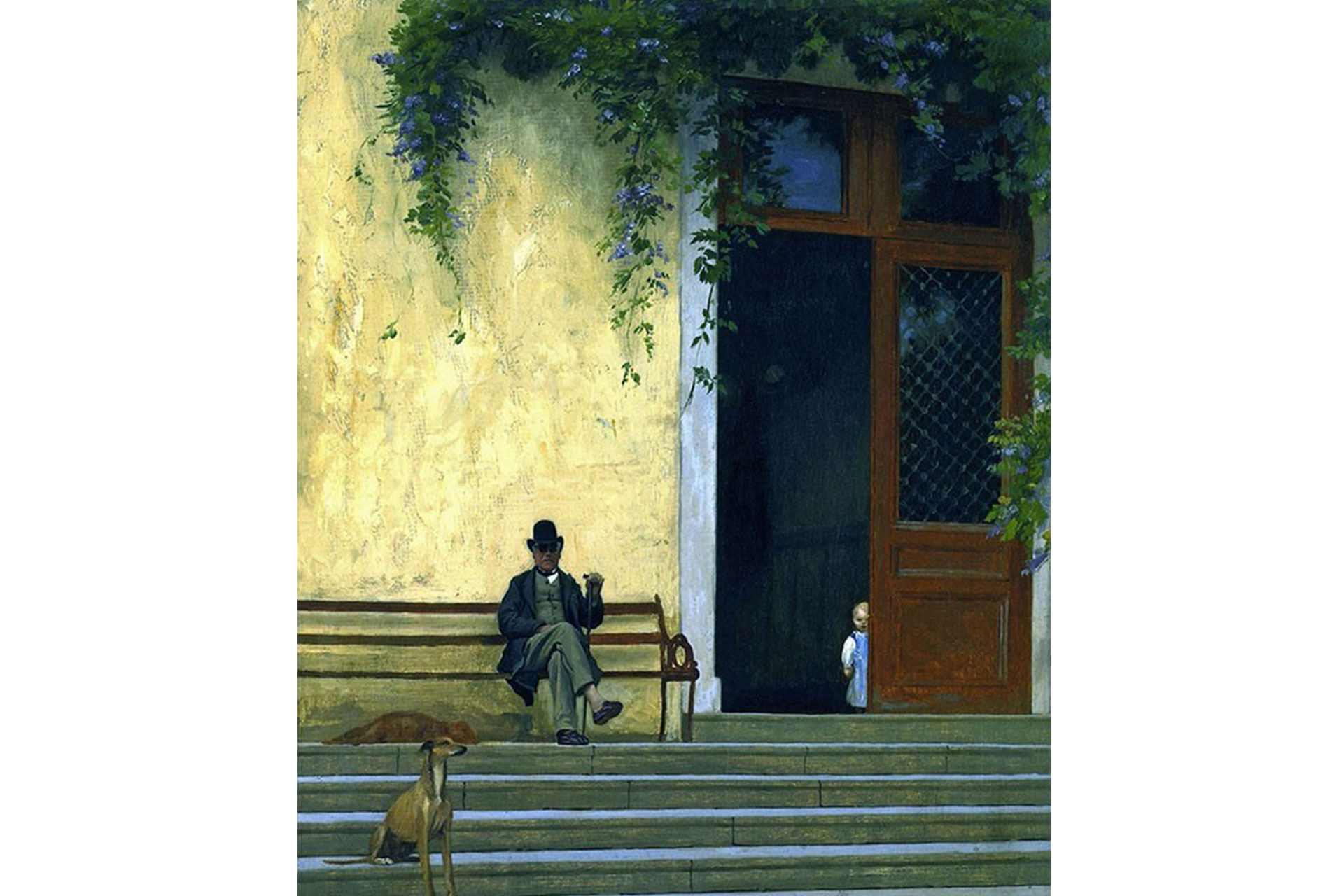

In the masterpiece of the orientalist Jean-Leon Gerome, known for his historical paintings, where he tests the past and the future through the threshold of his own life, son Gerome and his father, who are accompanied by the safe escort of two faithful dogs, are depicted as watchmen of the time, positioned on the doorstep of a house, leading the guests and residents of the house to a certain level in the face of life. While the fertile branches of spring cover the facade of the house, young Gerome, looking cute and curious in his white-blue overalls catches attention in the reassuring silhouette of the doorstep. At the doorstep, grandfather Gerome watches over and guards him, striking a gentle pose in his suit and his walking cane. The painting radiates a dynamic that questions the extent to which the audience can actually be there to witness a moment, through the anticipation that the figures create and the knowledge of the home originating from the scene it depicts.

One of the important representatives of the “Arts and Crafts” movement, Carl Larsson, who created masterpieces in multiple disciplines and whose works can be found in a collection exhibited in the Malmo Museum, is another artist, considered almost contemporary with Cezanne and Gerome. Also known for his idyllic family life-based compositions, Larsson, the father of three, portrays himself with one of his three daughters in this painting Brita and Me. The masterpiece, which draws particular attention to the joy of life that peaks on Brita’s smile on her father’s shoulders, with its objects of morale and tranquility in its interior details, as well as the vertical angle that the painter wholeheartedly used as an official full-length mirror, reveals itself as a time machine carrying ancestral memory, hanging on a wall inside the house and staring at us.

Similarly, the painting First Steps by Vincent Van Gogh, the world-famous artist of the “Post-Impressionism” movement, presents a popular specimen of the topic “fathers and their children”, his own rendition of his fellow artist Millet’s charcoal and pastel painting, of the same name, dated 1858. The painting, which can still be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, depicts how a family, who spends time in their peaceful garden in traditional costumes, embraces their offspring’s first steps with trust and love.

The French palette Edgar Degas, who is described as impressionist, but describes himself as a realist and can be considered contemporary with the mentioned painters, is a bit more melancholic in terms of his approach to his father, compared to others. Having studied law when he was young, and going after the images in the footsteps of Ingres, the artist, who is mostly known for his dance-themed paintings, depicts his father as taking on the full weight of the timbre, produced by the Pagan-Swedish violinist whom he is listening to. With his intense but consistent brush strokes that progress from brown to white, the painter reveals the intimate connection between the painter, the artist and his listener, while, in a sense, eternalizing the bond of respect and love he established between himself and his father in this composition, dated 1869, which seems both far and close at the same time.

The Italian painter, Antonio Mancini, who met Degas on his way to Paris for an exhibition in the 1870s and was praised by another well-known painter, John Singer Sargent, as the most valuable painter alive at that time, also depicts his father as a bust of a historical figure toward the middle of his career. Having probably portrayed his father at an advanced aged, who resembles a tree with his dignified look, in a coat, cap and as seated in his own studio, the artist, in this masterpiece, takes the lead of a unique observation, pushing that thin, dark, but genuine, and sincere line between the personal and the real. Being loyal to the Verismo, known as an Italian movement against the realist movement of the 19th century, the artist took his place in the history of art with two paintings exhibited at the d’Orsay Museum in 1876.

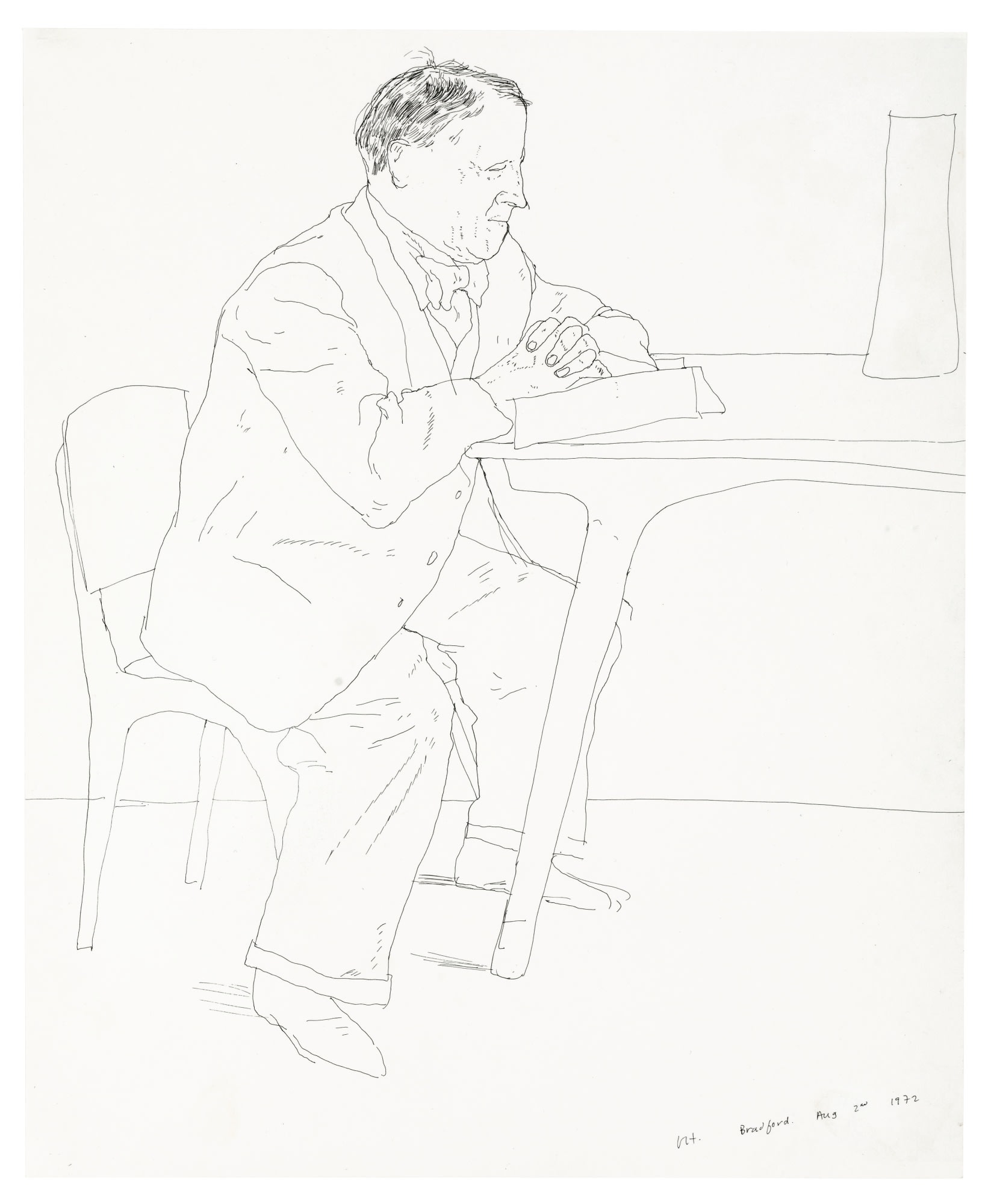

The topic of “fatherhood” seems to have been a source of active psychotherapy for many artists throughout the history of art. One of the artists who confronts both their personal and public histories layer by layer and form by form, by turning their consciousness “upside down” through their art, Bruno Lilijefors seems to have done everything in his power to portray his father in 1884 “in his own nature” through his depictions of modern and wild life in Sweden. Portraying his father with his feet stretched out in the peaceful silence of his house and among the flowering plants in the pot, Lilijefors favours remembering this hardworking, virtuous person whom he tends to remember with respect and admiration, as he reads through the paper with his special magnifying glass in front of the safe shadow of the stack of books, looking messy (for it is always in use). The refreshing light blue color of the paper keeps the painting strangely alive in a spiritual way as a hidden proof of the wisdom and humility that the painter inherited from his father.

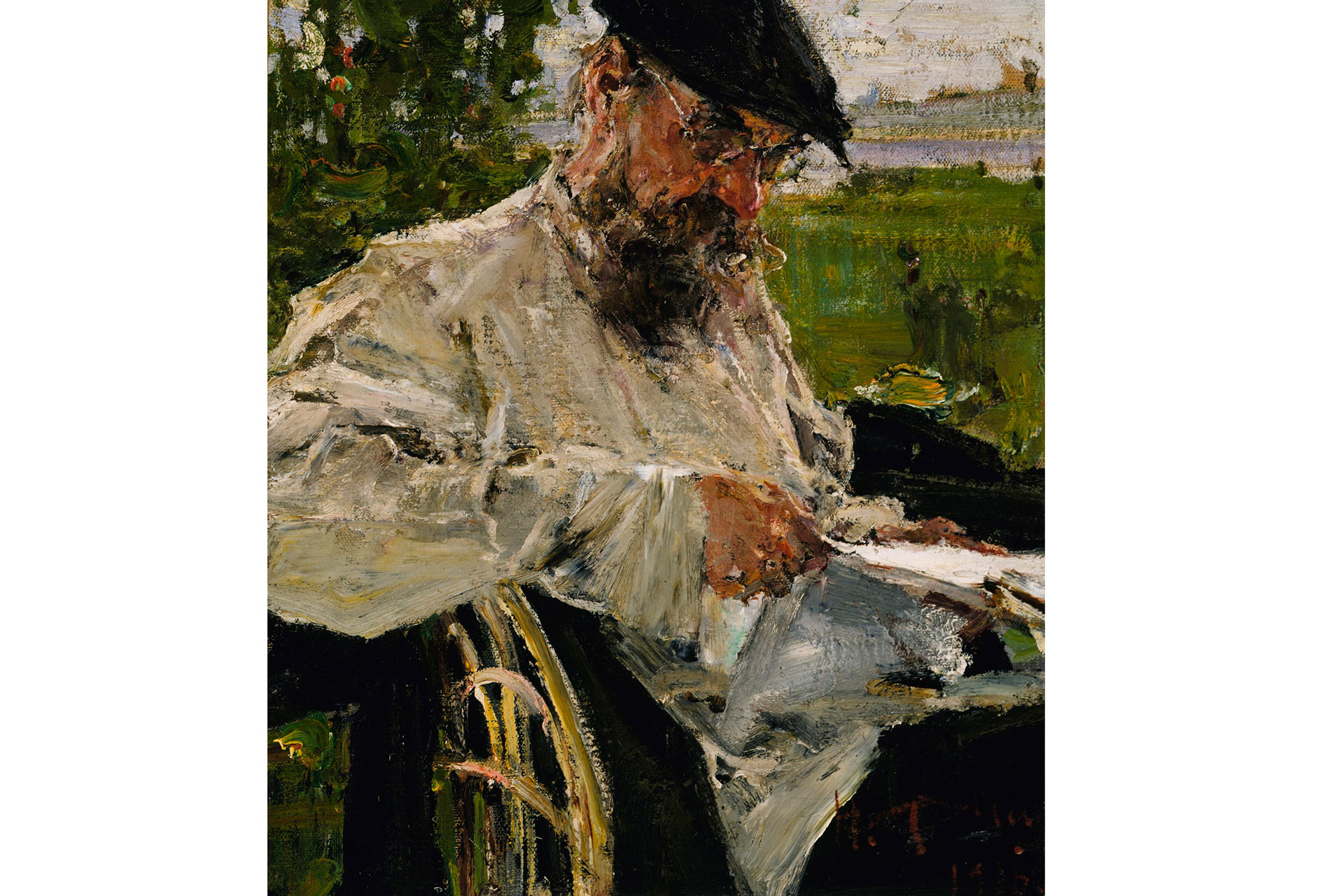

Likewise, the painter Nicolai Fetchin, who immigrated from another part of the world, Russia to the USA portrayed his father Ivan, a master of furniture and handicrafts and decorative creativity, who had always worked and produced, while enjoying the outdoors. In this masterpiece he made in Russia seven years before his migration to the USA, the painter draws attention with the thick brush strokes made with the tip of a palette knife, a special painting technique associated with him. The masterpiece, dated 1916, is still included in the collection of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art. Standing out with its vivid colors and solid details, the masterpiece tries to depict the artist’s father in his inner world as much as possible, and the distance in it reflects the artist’s admiration for his father.

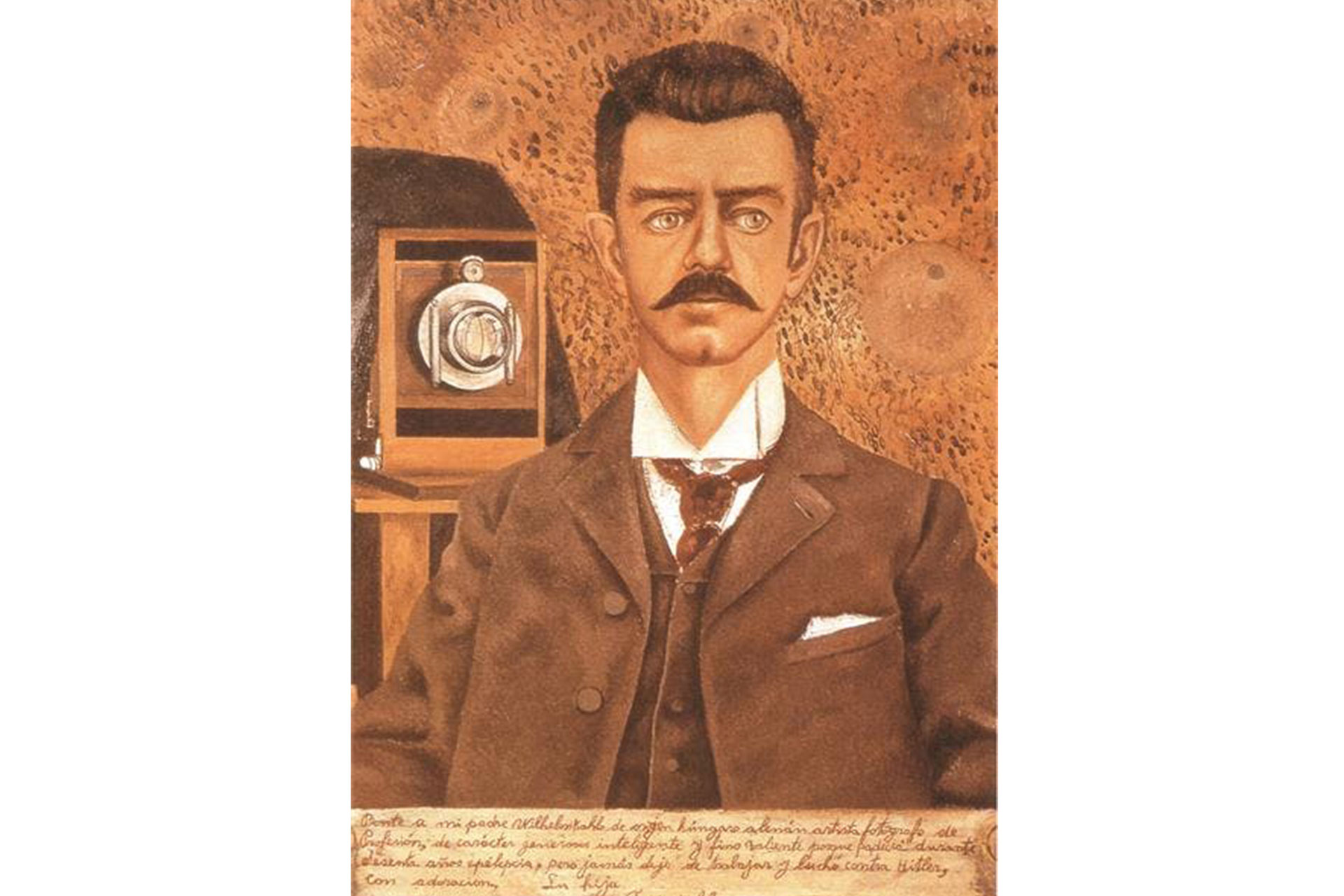

On the other hand, Frida Kahlo’s portrait of her father, dated 1951, turns the work of art into a kind of personal excavation site, through its details, admirable sensuality, as well as personal information and personal objects showing that she uses the painting as a diary.

In conclusion, in the history of art, fatherhood, parenthood or filiation has been an inexhaustible source of research and observation. When we conclude the article with a work of Pablo Picasso, one of the geniuses of art and the father of the cubist movement, made in 1971 when he had at least three children, it becomes clear that the topic is quite complicated and is a source of experience that can mess up the character of a person. In the masterpiece, exhibited in the Picasso Museum in Paris, the capital of France, a parent is depicted with their child in a surrealist and cubist approach.

In this respect, the history of art offers various narratives of parenthood delivered by many artists from David Hockney to Jonathan Lasker, Salvador Dali and Louise Bourgeois who adopted different styles to reflect the different aspects of fatherhood today.