It is May, the time of the year when we celebrate Mother’s Day, and with coronavirus reminding the entire world of the importance of science, education and health, one cannot help but remember Turkan Saylan, who inspired millions of people. Professor Turkan Saylan, physician, academician, writer, educator, and social responsibility volunteer.

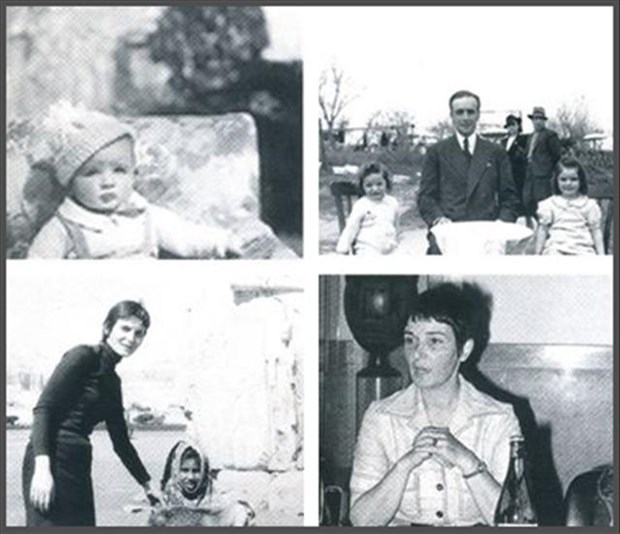

In the first years of the Republic of Turkey, Turkan Saylan was born in Istanbul in 1935 as the first child of Fasih Galip Bey, one of the first building contractors of the period, and Lili Mina Raiman. She would have four siblings, and perhaps, the merits she gained by being an “elder sister” would make her a good leader in her profession and in her life of volunteering, where she produced solutions for problems.

Her stern and oppressive parents would not even let her play with other children in the neighbourhood. Her life of wealth, which started in a big mansion, turned out to be a challenging one when her father’s business fell apart. They even had to rent out the mansion’s rooms. She wanted to be a village doctor throughout her life, and she achieved this goal. She heard the first call of freedom in the sound of the tram she took in Eminonu on her way to the Medical School. The medical badge she attached to her collar just in the first days of the school was her most precious piece of jewellery.

She got married before graduating from the university. She caught tuberculosis after giving birth to both of her sons. The second time was worse, as it spread to the bones, leaving her bedridden, and making her lie face down for eight months. She was not able to nurse her younger son. She raised her second son with cow milk in a village house where she lived with her mother-in-law in Kagithane Village. She had to wear a steel corset for the next two years; but she did not give up. Despite all these hardships, she graduated from Istanbul University School of Medicine in 1963. She always appreciated her mother-in-law, who looked after her and her children in those years.

The First One to Touch Leprous People

She visited Bakirkoy Psychiatric Hospital in 1958 as a pregnant student and she could not stand seeing the poor conditions of the leprous people. The attendant who took her there warned her not to touch the patients. But how would a physician cure a patient if she could not touch that patient?

That visit led her to choose to specialize in dermatological and venereal diseases (1964-1968). Young Turkan had found out after her extensive research that the disease was not transmitted by contact, and that it was treatable. Not only did she become the first person to touch a leprous patient in Turkey, but also she founded the Turkish Leprosy Relief Association in 1976. She played a role in the establishment of the dermatopathology laboratory and outpatient clinics forBehcet’s disease and sexually transmitted diseases . She voluntarily undertook the role of chief physician at Istanbul Leprosy Hospital (1981-2002).

Winner of the International Gandhi Award

She studied in England and she conducted studies in France. She assumed many roles such as the Head of the Dermatology Department of Istanbul University (IU) School of Medicine (1982-1987), Head of IU Leprosy Research and Application Centre (1981-2001), founder/head of IU Women’s Studies Centre, women’s health courses coordinator, and lecturer at Dermatology Clinic.

She acted as a leprosy consultant for the World Health Organization until 2006. She was the founding member and vice-president of the International Leprosy Union. She was also a member of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology and International Leprosy Association. She received the International Gandhi Award in India in 1986. She became the winner of many prestigious awards in Turkey and abroad.

Specifics get lost in a rough summary like this one. Finding doctors and nurses to work in the newly founded Istanbul Leprosy Hospital was a great challenge…She even had a workshop built in the hospital to make shoes for the leprous patients whose feet were deformed due to the disease. And she did all that despite financial challenges. She was a fighter who believed not having money was no excuse for not doing good deeds.

She Never Favored Her Own Children

The thing she feared the most was her diploma being taken away from her. She was no shrinking violet herself as she always said, “If they took my diploma away from me, I would go and get a new one”.

And her private life was not a bed of roses, either. She separated from her first husband. There were times when she could not see her children and had money problems.

But both of her sons learned the concept of “freedom” at their mother’s home. Even though Turkan Saylan used to say that she neglected her children, “She did not cook for us three meals a day, but she broadened our horizons”, say her sons Cinar and Caglayan Orge, as they reminisce about their mother. They say that Turkan Saylan, who opened up her house to the friends of her two sons going to university, who did not have a place to stay, treated all of them equally and she would not give her own sons any extra scoop of soup, even secretly.

Her sons, one of whom is a physician like she was, and the other a graphic designer say the following for their mother:

“We did not feel that she was biologically our mother. We were like friends. We were like other children whose lives she changed. She treated us all on an equal footing.”

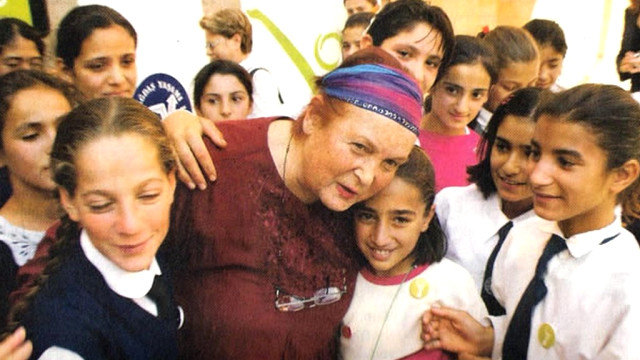

Lifeblood For Snowdrops

Until her death in 2009, Turkan Saylan fought for a modern society, equality of opportunity in education, and worked really hard to provide girls with proper education and teach them a decent trade. The Association for Supporting Contemporary Life (CYDD) she founded supported “snowdrops”, a name given to school girls.

“Mom did not think she was a hero. She considered it to be an ordinary, routine duty, and she did not let us think the opposite way”, say her sons, proving that Turkan Saylan was a woman who never looked for appreciation at home or in her private life.

Her younger son, Cinar Orge, who is a physician, describes the funeral of her mother spontaneously attended by thousands of people without any special planning:

It was the first time in my life I had seen so many people radiating benevolence and good will gathered together. So many were crying. They were not sobbing; there was a drop of tear running down their cheeks. It was a sad but a sweet farewell.”

She did not neglect her own children; she embraced thousands of children as her own.