The art market, dependent on the endless auctioning of this mortal world, is currently watching the “Crypto-Art” and its stars with the complacency and insurance offered by the digital currency “Bitcoin”. However, it must not be forgotten that crypto-art has art history to thank for its astronomical journey into the present and the future.

In these moments when you are running your eyes over random things, you have happened upon this mortal essay on the “Crypto-Art” market, which is now worth millions of dollars electronically across the world, within seconds of surfing, and its reflections on (contemporary) art history.

“Crypto” has now become a word charged with negative connotations that constantly floats in the air like the COVID-19 virus, bandied about in political news and discussions in our country.

If a person or institution uses the word “crypto” to refer to its competitors or affiliates, the intent is usually to vilify or denigrate the persons or communities they marginalised. Therefore, in order for a work of art to be integrated into the crypto-art movement from the outset, there needs to be courage, licence or cultural status as such (including the artist with or without an anonymous signature) to describe it along those lines.

For example, if you are a high-profile media figure in the public eye, an academic or a global critic with a large number of followers and readers, it makes everything in this “market” even more formal. However, the stock market of electronic art sees it as a new gold mine (resource) for digital labour capital and context rather than a disadvantage.

In a way, the method has always been the same since works of art could be reproduced. The “digital” quintessentially requires a certificate of “uniqueness”, an exclusivity of “limited availability”, and a physical or conceptual packaging design for the benefit of the “market”.

Carrying the digital into such an aesthetically exclusive domain within the reach of a select few is already a common sight in today’s popular auctions. There is a market for everything now, from bubble gum rolling papers featuring old cars and football players to plastic figurines, from metal car models to stamps, from cards signed by film stars to objects or instruments signed by musicians or collections of sports statistics cards and they all burst with activity. To sum up, the “thing” does not have an intrinsic value; it flows from the spontaneity that surrounds it. It owes its value to our willingness to make it part of our lives or bandy it about in our tongues and our requirements, or it already claims a place for itself in the future as a valuable commodity.

As a matter of fact, curators or authors or critics, art dealers, galleries, and those at the top of the celebrity chain with millions of followers have been doing exactly the same thing voluntarily or involuntarily, perpetuating the cycle of this “implicit” valuation and devaluation for almost as long as art history existed: Movements are started, they are filled with signatures, theses and determinations, then these are eviscerated with new interpretations and new theses, to be refilled with brand new conceptual or numerical packages and even burnished, and polished and marketed with references to elite and exclusive museums and collections. A shining example of such an extreme approach towards art in recent history is Piero Manzoni, who put his own excrement in a can in May 1961 (https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/manzoni-artists-shit-t07667) and displayed it for all to see. Whether physical or not, the “auctioning” of works of culture and art, and their promotion through word of mouth, often adds to the symbolic value of the work or artist in question.

Continuing the emphasis on the implicit and the cryptic, and considering the “screen” as the new platform for art to disseminate itself, what we have on our hands is the “plastic art” evolution, transitioning from photography to video, from movies to the “electronic canvas” in the last century. In this context, too, one can recall examples of classical or contemporary artworks reproduced using three-dimensional modelling techniques. This was exemplified in the statue of David by the Renaissance master Michelangelo, which the contemporary artist Serkan Ozkaya from Turkey tried to take to the 21c Museum in the USA (http://magazine.art21.org/2012/08/17/double-or-nothing-an-interview-with-serkan-ozkaya/serkan-ozkaya-david-inspired-by-michelangelo-21c-museum-6/) and attempted to exhibit at the Istanbul Biennial.

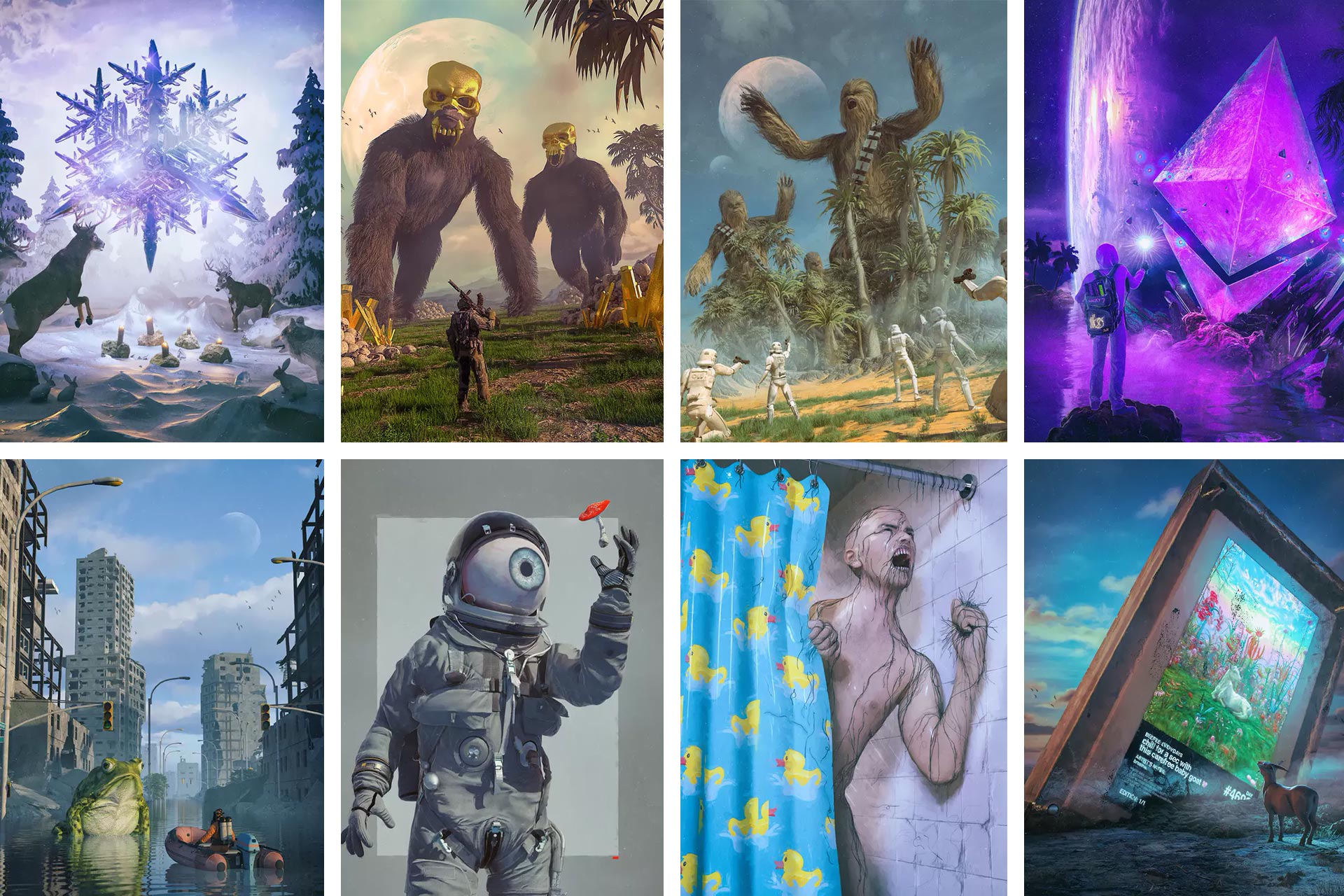

One of the most conspicuous personalities criticising this reproductive, liberal, wild capitalist attitude measurable by price and merit, and at the same time benefiting from it, is the Polish US art icon Andy Warhol marketing his own images of truth to the world in his “Factory”. Following the same trail, a cyber factory of Beeple, a very popular “digital crypto artist” (Mike Winkelmann / https://www.beeple-crap.com/about) who managed to sell his “five thousand days in the digital world” for 70 million dollars (minimum) (https://www.beeple-crap.com/everydays), is now active / online and when you visit his webpage, you see a catalogue that is almost indistinguishable from a digital marketing resource. Beeple’s work represents an admirable electro-effort, that is at times photo-realistic, and often gothic, grotesque and hyper-realistic, fuelled by pop culture icons and anti-icons (https://www.beeple-crap.com/everydays?pgid=kdyix8la-george-floyd_128).

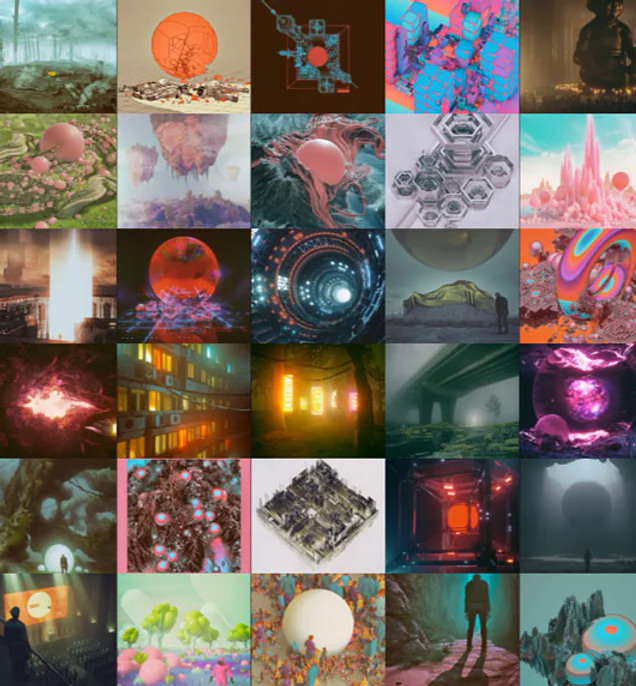

If we are to mention figures other than Beeple, who is originally from Southern California and works as a creator-designer with world-famous brands on a client-supplier basis, a global example of such a generous market is the digital art medium Artstation on the internet that promotes the visibility of artists through trade (https://www.artstation.com/about). If we return to the logic of the factory, works produced by the artist in his own workshop in collaboration with a crowd of names, almost acting like a composer, are manifested strongly in the deductive production techniques of brand stars like Ai Weiwei or Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst today.

At the end of the day, the auction is constantly updated by both the artist and the market (https://niftygateway.com/stats9). As we have just said, the art’s drive to exist in digital media, its shape-shifting tendencies, whether excellent or popular or not, coupled with a press that is ready to act as a puppet (voluntarily) reduces it to an inventory item within the context of a “win-win” relationship.

Just like the works of the contemporary British painter David Hockney (https://www.hockney.com/index.php/works/digital/ipad) with large numbers and small pixels he has been giving us for some time via his iPad, or the works of Memo / Mehmet Akten (http://www.memo.tv/#bio), an academic and digital artist born in Istanbul in 1975, which we have seen displayed in some exhibitions in Turkey.

This “crypto” state of contemporary art inevitably reminds me of the journalist Clark Kent, “crypto” / anonymous, an orphan who fell to Earth from the planet Krypton i.e. the fictional Superman / Kal-el figure.

Crypto-art always needs the global network of the internet / telecommunication network to disguise and save the earth from itself, and it engages in a love-hate relationship with popularity. And we must just marvel at his uncontrolled genius with involuntary addiction, at his personality and the things he does, just like the visions we have in our dreams. This is because the art market, dependent on the endless auctioning of this mortal world, is currently watching with great relish the “Crypto-Art” and its stars with the complacency and insurance offered by the digital currency “Bitcoin” that we often hear about these days. However, it must not be forgotten that crypto-art has “organic art history” to thank for its astronomical journey into the present and the future.

I am going to be a bit partial now: But the most ironic proof I can give in this sense has to be the Belgian “all-out artist” Marcel Broodthaers (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcel_Broodthaers), whose dates of birth and death happen to be the same as mine: 28 January 1924-1976.

Broodthaers, the poet, director and journalist who even designed his own tombstone before he died – made by the Belgian sculptor, the artist Karel Van Roy – was a member of the “Revolutionary Surrealist” movement, experiencing his own existence like a work of art, with his fingers dipped in almost all forms of art imaginable.

It seems, as evidenced by the clicks, that this trend, boundless and plural, is both revolutionary and evolutionary with a solid foot in the online world.